We are all very familiar with the term “organic” these days – not least from our day to day food shopping experiences. Organic wine, if accredited – like foods – is made with no added synthetic pesticides or herbicides – or any other synthetic chemicals such as “artificial” fertilisers.

As mentioned in the previous blog on additives Wine Trust Blog – Additives – July 2015 – even some organic wines though, will then include the preservative sulphur dioxide (SO₂), although a number of food items will also use this agent (marked as E220 on the back label) – such as dried fruits and soft drinks.

As with biodynamic wines, true organic wines are part of an accredited organisation such as The Soil Association of Britain, which will have its own code of practice and regulations for members.

In reality though, many producers these days regularly operate to what they describe as “organic principles” but will not actually be a bona fide member of a formal organisation. In France, they term this as “Lutte Raisonnée” – or “reasoned struggle” – sometimes accompanied with a ladybird symbol. These producers are not strictly organic but will ensure that as many of their practices as possible adhere to natural processes. However, and very practically, if they face a particularly difficult year where rot, for example, is highly prevalent – and the only way to avert a complete ruin of their harvest is by spraying a herbicide – then they will use it.

Maybe more practically, as one Vigneron once recited to me in the Rhône, “How can I be “organic” when my neighbour regularly sprays his vines (with synthetic treatments) and the spray cloud drifts across onto my plants!?”

Today, therefore, “sensitive” vine growing and winemaking is commonplace and true biodynamic producers are much rarer, but include some big names, including Domaine Leflaive in Burgundy, Chapoutier in the Rhône and Fetzer in California. They are also becoming more popular with smaller and more artisan producers as the fashion for “Natural Wine” grows (again please refer to the Additives Blog). But what then makes a biodynamic producer, and what is different from simply being organic?

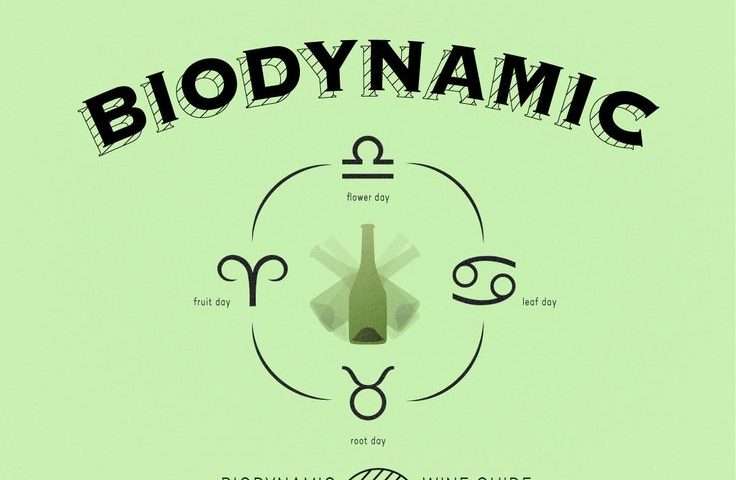

Biodynamic wine producers are by definition already organic, but then take matters significantly further. This was nicely summarised by Jasper Morris MW who said, “An organic wine making approach is axiomatic, but biodynamics seeks to go further. Central to the issue is the calendar which divides days into Flower, Fruit, Leaf and Root categories according to the influence of the moon and stars on the Earth’s natural rhythms.” So there you are!

- Fruit – Harvest time

- Root – Pruning

- Flower – Leave the vine to produce the fruit

- Leaf – Water the vine

Again to paraphrase: Winemakers who practice biodynamics believe that by combining ecological self-sufficiency with modern agro-ecology you create a living, inter-connected system (most importantly the living soil and organisms within it – including bacteria) and the immediate micro climate the vines exists in, which results in organic, healthy fruit to harvest.

These four categories – Fruit, Root, Flower and Leaf – are where the correlation to the moon and stars comes into effect. The biodynamic calendar is split into these categories which each represent the optimal time for a particular stage of the vine planting, vine growth and health and influences on the best time to harvest.

The origins of biodynamism go back to the founding philosopher of the practice – the controversial Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925). This theory evolved out of his broad philosophy of anthroposophy, which embodied the understanding and interconnection of the ecological, energetic and spiritual forces in nature. Many have taken up his thinking in a very proactive manner with regard to vine growing and winemaking.

One of the trade’s greatest biodynamic protagonists is the winemaker Monty Walden (pictured below) and he explains more about the practice in his book Best Biodynamic Wines as “biodynamics involves spraying the vines with a series of “preparations” mostly derived from plants, which have been “dynamised” (ie stirred well). The dates and times of day of these applications depend on the lunar cycle. Another important preparation, horn manure 500, is made by burying manure in cow horns in the vineyard between autumn and spring”. Horn Manure 500?

Yes, horse manure aged in cow horns buried underground is one of the fundamental biodynamic treatments. And there are many more – here is a list of the main practices:

Biodynamic preparations

For a vineyard to be considered biodynamic the wine-grower must use the nine biodynamic preparations, as described in 1924 by Rudolf Steiner, although it is worth noting that Steiner himself never actually farmed. These are made from cow manure, quartz (silica) and seven medicinal plants. Some of these materials are first transformed using animal organs as sheaths (NB: the animal organs are not used on the vineyards). Of the nine biodynamic preparations three are used as sprays (horn manure, horn silica and common horsetail) and the other six are applied to the vineyard via solid compost.

- Preparation 500 – Cow manure is buried in cow horns in the soil over winter. The horn is then dug up; its contents (called horn manure or ‘500’) are then stirred in water and sprayed on the soil in the afternoon. The horn may be re-used as a sheath.

- Preparation 501 – Ground quartz is buried in cow horns in the soil over summer. The horn is then dug up; its contents (called horn silica or ‘501’) are then stirred in water and sprayed over the vines at daybreak. The horn may be re-used as a sheath.

- Preparation 502 – Yarrow flowers are buried sheathed in a stag’s bladder. This is hung in the summer sun, buried over winter and then dug up the following spring. The bladder’s contents are removed and inserted in the compost (the used bladder is discarded).

- Preparation 503 – Chamomile flowers are sheathed in a cow intestine. This is hung in the summer sun, buried over winter and then dug up the following spring. The intestine’s contents are removed and inserted in the compost (the used intestine is discarded).

- Preparation 504 – Nettles are buried in the soil (with no animal sheath) in summer and are dug up the following autumn and are inserted in the compost.

- Preparation 505 – Oak bark is buried in the skull of a farm animal, the skull is buried in a watery environment over winter, then dug up. The skull’s contents are removed and inserted in the compost (the used skull is discarded).

- Preparation 506 – Dandelion flowers are buried in a cow mesentery (intestine). This is hung in the summer sun, buried over winter and then dug up the following spring. The mesentery’s contents are removed and inserted in the compost (the used mesentery is discarded).

- Preparation 507 – Valerian flower juice is sprayed over and/or inserted into the compost.

- Preparation 508 – Common Horsetail made either as a fresh tea or as a fermented liquid manure is applied either to the vines (usually as a tea) or to the soil (usually as a liquid manure).

This also usually coincides with the use of more general organic practices such as allowing vetch to grow in between vines to provide top soil cover, hold moisture and avoid soil compaction. In addition to use all cuttings and natural vineyard waste in a composting regime. When working with (Angelo) Gaja in Barbaresco, Piedmont they were embroiled in a programme to develop a broader population of earthworms which were then being introduced throughout their vineyards – just to take another example.

Today, there are more than 450 biodynamic wine producers worldwide. For a wine to be labelled “biodynamic” it has to meet the stringent standards laid down by the Demeter Association, which is an internationally recognised certifying body. Demeter biodynamic wine certification

Not unsurprisingly this approach and discipline also encourages a lot of sceptics – from those who see it simply as “emperor’s new clothes” to those who see it as nothing short of “voodoo”. And as there has been limited empirical scientific study to compare biodynamic viticulture with conventional methods a lot of the conclusions drawn are anecdotal and usually from those already practising biodynamism. Waldin simply states – and not without foundation – that the discipline seems simply to work and that better and more individual wines are produced. This then brings the whole concept head on into the very French notion and philosophy of “terroir” and how this influences both quality and individuality in wine – a topic for another blog I think!

There is absolutely no doubting the conviction biodynamic producers have in this philosophy and discipline. I worked with Michel Chapoutier (Hermitage) for four years and he was utterly convinced that biodynamism had transformed his vineyards in the Northern Rhône over a 20 year period. Likewise, the late Anne-Claude Leflaive was equally passionate about how this had improved her vineyards and wines at Domaine Leflaive in Puligny-Montrachet. In fact Anne-Claude lived a lot of her general life by the biodynamic calendar. They both felt that the natural environment created was a positive influence in offsetting diseases, promoting greater and more even ripeness and prolonging the health and life of the vine.

Maybe a final caveat to consider though is that the smaller the producer, the easier it is to adopt and put biodynamic principles into practice. It is hard to see how any large, more mass market producer could possibly make biodynamics work on a practical basis.

On a linked note you may have also heard of the term “sustainability”. This tends to refer to a range of practices that are not only ecologically sound, but also economically viable and socially responsible. “Sustainable” producers may farm largely to organic, maybe even biodynamic principles, but have flexibility to choose what works best for their individual estate. They may also focus on energy and water conservation, use of renewable resources and other issues – such as cardboard and bottle recycling. A number of regional industry associations are working on developing clearer standards in this area. In essence this whole area is ever evolving and (re)defining itself.

On a personal note I have no issue with any wine made organically or biodynamically as long as it is not a cover for inflated prices (and maybe egos!). Nor should it be a cover for poor winemaking per se. And if in the process these producers are recreating an environment which is more sustainable and healthy – then this must be recognised and applauded.

In fact we have many wines in the Wine Trust selection which are made to “organic principles” – and some are fully accredited. A good example is the excellent Adobe Carmenère from Chile Adobe Carmenere. Another top flight example is the outstanding Chianti Classico from Fontodi Fontodi Chianti Classico who are working towards full biodynamic accreditation. Other fine organic and biodynamic wines include:

Poderi Nebbiolo d’Alba

Dao Ribeiro Santo Reserva

Pouilly Fumé Prediliction Jonathan Pabiot

Pouilly Fumé Jonathan Pabiot

Cigalus Gérard Bertrand

Chablis Domaine Collet

Herdade Ciconia

As ever a subject matter which will remain front of mind at Wine Trust!