Additives in wine: What goes into the making of wine and may be termed an “Ingredient”, or “Additive”? What is “Natural Wine”; wine deemed “suitable for Vegans and Vegetarians” – and how might this all matter to the wine drinker.

Fundamentally, wine is made from the fermentation of the juice from freshly gathered grapes. This is where it all starts because when the winemaker analyses the juice, he/she will make judgements as to whether the component parts – most importantly the sugars and acids – are of the concentration and balance they ideally require.

Even at this early stage most regions and producers are allowed – but only if required (and this still has to be sanctioned by the local governing bodies) to use additives – such as (more) sugar, or acid, or to reduce the acidity by the addition of an alkaline agent. Any addition of sugar is to increase the potential level of alcohol, not to make the wine sweet.

In a perfectly ripe and even growing season the juice will not require any adjustments or additives at this stage – so this issue tends to arise when the growing season has been poor and the grapes are very high in acid (potentially sour) and low in sugar, or paradoxically, are super (too) ripe and too low in acidity and lacking refreshment and balance. But I must stress – and this will be a theme throughout this blog – it is down to the winemaker and the commercial pressures they face along with their own beliefs and philosophy. However, if you are mass market, bulk wine producer you will want – more likely demand – that wines are both consistent and above all stable, so for them the role of additives becomes a very functional and economic matter.

It must be stressed that there is nothing wrong in adjustments if the resulting wine is the better for making them. Sugar is fundamentally important as it is the fuel for the whole fermentation process and the higher the sugar level, usually the higher the alcohol level will be when the wine is fermented out dry. Acidity is also essential as it is the foundation of the balance and refreshing (mouth watering) nature of any wine.

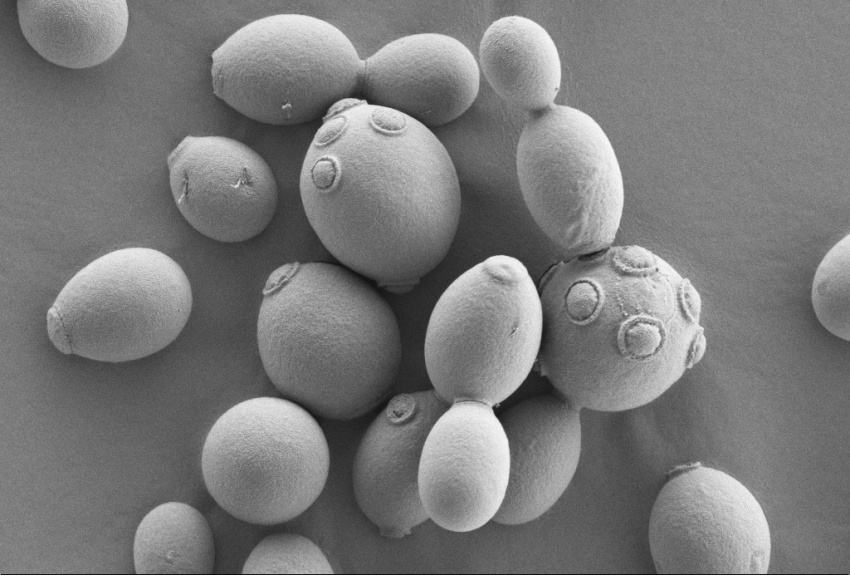

The other vital ingredient is yeast. This tiny organism feeds on the sugar and produces the alcohol as a bi-product, along with wine flavours and carbon dioxide (CO₂) gas. Again yeast can live naturally in the atmosphere, or on the skins of grapes. Equally it can be added by the winemaker as a “culture” (just as a baker would do) – this is called inoculation. There is absolutely nothing wrong in making wine this way it must be stressed – in fact for some producers it is essential to ensure consistency in their product – in Champagne for example.

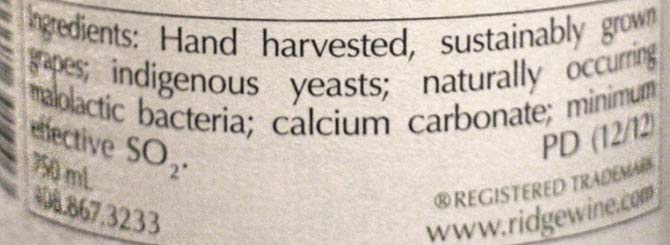

For a more “natural” winemaker they would only use the yeast which exists in their vineyard as they feel it is an essential element in the expression of the wine. If you see the term “wild” ferment on a label it means for sure the wine has been made this way. Equally, more natural winemakers will not wish to adjust the juice in the first place unless forced to do so by a truly challenging vintage.

At this point we come to the use of what is one of the most traditional and frankly essential additives of all – Sulphur Dioxide (SO₂). Coded by the EU as E220 on food back labels, this is used widely in both the food and drink industries as it is powerful anti-oxidant and antiseptic. However, it has become the source of much debate regarding additives and allergies – so much so that all bottles of wine are now required by law to display the term “contains sulphites, or sulfites” on the back label. For some people they may have an allergic reaction (maybe only a small one) to sulphur so this is an important consideration.

Wines with total SO2 concentrations below 10 parts per million do not require “contains sulfites” on the label by US and EU laws. In the EU maximum levels are 150mg/lt for dry red wines and 200 for dry white and rosé wines and 300-400 for sweet (depending on just how much residual sugar they have). The reason reds are lower is that the tannins they contain (which cause that gum/teeth drying sensation) are themselves (already) antioxidants. Sweeter wine levels are higher to neutralise any potential yeast which may be in the wine (or get in) and start off another unwanted fermentation in the bottle.

In low concentrations, SO2 is mostly undetectable in wine, but at free SO2 concentrations over 50mg per litre, SO2 becomes evident in the smell and maybe the taste of wine – and in these instances may even be mildly unpleasant. And some people are finding that they might suffer a reaction to higher levels of sulphur (such as headaches) so it is an issue to be taken seriously.

Natural wines and winemakers use low or no levels of SO₂, thereby reducing this potential problem, although this practice may lead to other issues. To quote Isabelle Legeron MW – a champion of natural wine – “Organic and Biodynamic certifying bodies are more stringent, but natural wine is the strictest of all, with most producers averaging under 30mg per litre for reds, 40mg for whites and 80mg for sweet wines. Some growers use none at all”.

There is no formal definition of “natural wine” but, in general, these are wines made with minimal chemical and technological intervention in the growing of grapes and then the making of the wine. All natural wines tend also to be farmed organically as a minimum, and many growers are biodynamic in the vineyard as well. We will explore this viticulture topic in another blog by the way.

Personally, I have tasted a significant number of “natural wines” in recent years and would say that from this anecdotal research have found many of them to be underwhelming and in some cases simply faulty. The big issue is these wines will oxidise more quickly. Natural does not automatically mean “better” in my view. And this doesn’t mean we are not continuing to look for a natural wine for WineTrust, because we are.

But let’s move on to how the wine is finished or stabilised, as this opens up another topic of debate and interest – not least for vegans and vegetarians. When a wine has finished being made and is ready to be bottled, many winemakers will want to ensure that the wine is both clear and bright, but also stable and not prone to any further microbiological activity. This can be done to varying degrees and rigour.

The main processes used are finings and filtration. Finings are materials which clarify the wine. They are added in various forms and through the joint process of gravity and (opposite) electrical attraction bind with the hazy solid matter and unwanted organic compounds in unfinished wine (called colloids by winemakers) and take them away to the bottom of the barrel or tank, leaving beautifully bright, more rounded wine above, which is then drawn off and bottled.

The issue for vegetarians and vegans is that the materials used could have originated from an animal or even dairy source. The most traditional of all agents used for red wines was/still is egg white – albumen. Other materials used include milk (casein), isinglass, bentonite (earth) and gelatine. Again the issue is that some of these are animal based – eg isinglass from fish. But it doesn’t mean they all are, so producers looking to make vegan/vegetarian friendly wines will use non animal based agents instead – or not use any finings at all.

I must stress here that irrespective of the producer’s and consumer’s own philosophy about finings, even if an animal based agent is used no trace of it will remain in the bottled finished wine. This is why they are not considered in law to be “ingredients”.

After fining a wine the final step for many is to filter the wine through a fine membrane, which ensure all unwanted particles and microbiological residues are removed – in other words making the wine completely stable. This is critical for producers of bulk mass markets wines whose nightmare scenario is a product recall on a mass scale. But for smaller, more niche market producers they fear that if you (over) fine and filter a wine you also take out vital flavour and structural ingredients which, at best, make the wine blander in flavour. For winemakers who go down the route of “unfiltered and unfined” wines – often advertised on their labels – there is a retrospective emphasis on increased attention to detail and cleanliness in the production process to ensure the wine remains stable (which is by no means difficult) but tends to be restricted to those who make wine on a smaller scale, and also maybe adhere to more natural processes in general.

In reality the vast majority of quality winemakers set out to ensure that they use the minimum levels required of SO₂, finings and filtration (and additives in general), but will adapt depending on the nature and conditions of each individual harvest. And also a fundamental rule – the healthier and higher quality the grapes you use in the first place – and the more hygienic you are with your practices – the less need there is for all these “belts and braces” (for want of an expression).

And finally … there is another possible additive to mention – alcohol itself. You may be familiar with the term “fortified wine”, which as the name implies is made by the extra addition of alcohol (usually grape spirit) above and beyond the level that is produced naturally during fermentation. Originally used as a form of preservative (which alcohol can be) these wines have been adapted over the centuries to be some of the finest on the planet. Port and Sherry are probably the most famous. It is another example of how what might be termed working with a wine contributes to not only greater stability and consistency, but improved quality and diversity of style.

Modern winemaking is the most advanced and consistent it has ever been. Today wine production standards are indeed high. Wine still remains a relatively natural product, but it does have additives and processes which may raise questions for certain people. Rules are in place to safeguard them and labelling is advancing all the time to provide the information they require to make a purchasing decision. At WineTrust we are encouraging all suppliers we work with to provide us with production information we need to keep you informed in turn.

Nick Adams MW – July 2015