Of all the countries in the Old World Italy is one of the oldest, and arguably the most individual in terms of indigenous grape varieties and spectacular (often strongly secular) regional variations and styles. It is also complex – and trying to condense this amazing vinous kaleidoscope into a manageable summary is not easy. But I have such a love for the country and wines that I thought I would give it a go – over three separate blogs. Inevitably I have had to exclude as much as I included – and provide highlights which I believe are more pertinent to the UK Italian wine lover and drinker.

Wine Trust – from day one – has championed Italian wines and their selection has real depth and breadth; so, I will pick out some highlights as we go along.

Introduction

Italy vies with France each year as the single largest wine producing nation in the world. Like most European countries Italy is experiencing a decline in domestic sales and as a result has to focus more on exports markets than ever before.

As a country, Italy (formally founded 1861) only became a united entity in the 1870s and there is still some “fragmentation” between regions now, with many operating as quasi countries within a country, so to speak. Overall, there is a significant division between the “North” and the “South” (by that south, south of “the Rome line”) and a clear disparity in wealth between these areas, with the north far more industrialised and wealthy than the south.

The delimited DOC(G) production areas were first defined in 1963, but were quickly challenged by those producers who felt their regulations were too constrictive. This led, indirectly, to the creation of the “super Tuscan” category, where certain producers openly flouted the rules and proudly sold wines at the basic “Vino da Tavola” level. Today there are over 340 DOCs and over 80 (and growing) DOCGs, with the generic IGT (Indicazione Geographica Tipica – or IGP now) underneath.

Italy also uses terminology peculiar to the country – not least “Classico” referring to the heartland – or supposedly best vineyard areas within a DOC(G) – eg Soave, Chianti, Valpolicella. The term Riserva usually refers to higher quality selected wines (often with more oak and bottle aging) but does not carry the definition or legal obligation as is found in Spain for example. Passito refers to the Italian speciality of air drying the grapes (for 3-5 months) to increase levels of sugar and concentration (and in the case of black grapes, tannins and colour) with the resultant wines.

In vine growing and winemaking terms, Italy is unique in that, with two exceptions, the grapes grown and wines made are often unique to that declassified area – and not found anywhere else in the country. It is on this basis that this paper and review is based. Remarkably Italy uses hundreds of different grape varieties to make wine, but we will focus on the main and more famous examples.

The country is so elongated that at its most northern tip you are level with Burgundy (to the west) in France, whilst at its most southern point you are below the North African coast. In addition, large parts of Italy are mountainous/hilly, which combined with its ever close presence to water makes for an incredible series of micro- climates. In addition, the soil is very old and weathered so little surprise that nearly every region’s wines are so individual.

The Exceptions

Two white grapes, in particular, buck the Italian trend and are found in many parts of the country – these are Trebbiano (aka Ugni Blanc in France) and Pinot Grigio (aka Pinot Gris).

Trebbiano makes medium bodied, crisp and relatively neutral white wines, and is a good “stocking filler” in a blend or a source of cheap and unassuming varietal wine at the entry price level. It is widely grown, most especially in areas such as Tuscany, Veneto and the Central East region. Certain clones – such as those found in Soave – are said to produce wines of greater character.

Pinot Grigio is so named after the grey or rusty colour the grape develops when it ripens. This why if you leave the skins in contact with the juice you can make a rosé – or rosato – Pinot Grigio. A mutation originally from Pinot Noir this grape is grown all over Italy, from the lower Alps in the North to the hot flat lands on Sicily. The very wine (name) has become an important brand in the export markets, but there is a great diversity of styles. At worst – such as from over cropped, warm plain land vineyards in the Veneto – it is neutral and anonymous. However, in certain cooler areas, with lower yields (eg Friuli in the North-East) it can take on some real and aromatic fruit qualities, such as quince, comice pear and soft spice notes. An excellent example of this is the vibrant Ponte del Diavolo on the Wine Trust list – worth that extra spend to gain so much more character.

Pinot Grigio – Ponte del Diavolo

The main regions; their grapes and wines

Part I – The North

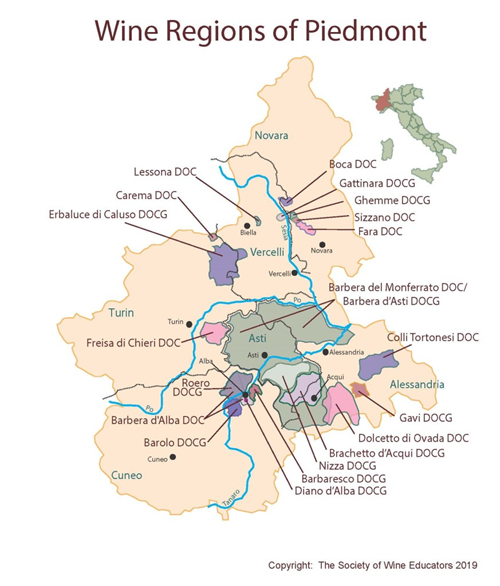

- Piedmont(e) – North West

A wealthy and historic area which arguably boasts Italy’s most famous and finest red wine – Barolo, although its near neighbour Barbaresco makes wines of equal quality. Both the areas are quite small, with Barbaresco being even smaller at only a 1/3rd of the size of Barolo – and there are sub districts and single vineyards within them which are most prized. To put this into some sort of context, Barolo (origin 1840’s – DOCG 1966) is only 1700 has large (which is only 1/10th the size of Burgundy) and Barbraresco – origin 1890 – (DOCG 1980) (at 640has) is really small.

Examples and sub districts include

Barolo

- Serralunga – Falletto | La Serra

- La Morra – Cerequio | Brunate

- Barolo – Bricco Viole| Cannubi

- Castiglione – Fiasc | Monprivato

- Monforte – Cicala | Santo Stefano

Barbaresco

- Barbaresco – Rabajà | Asili

- Neive – Santo Stefano

- Treiso – Pajorè

- Alba

Barolo require 3 years aging before release (by law); for Riservas 5 years | Barbaresco 2 years, Riservas 4 years

With cold and snowy winters and warm dry summers this region prolongs the ripening season and teases out the most powerful, yet delicate flavours and aromas of the Nebbiolo grape. This grape’s paler red colour belies remarkable levels of tannin, acidity and power, but also perfume and finesse (classically referred to as “tar and roses”). The top wines need 10-15 years to come round and show their best.

In simple terms, producers tend to be split between those who are loosely termed at Traditionalists – long aging, old wood (eg GD Vajra) and Modernists shorter time, new often French oak (225lt) barrels (eg Gaja, Aldo Conterno); with those in between (Giacosa)

In broader more regional appellations you can also find the Nebbiolo grape, such as in d’Alba and d’Asti, named after the two main cities in the area. In addition, the red grapes Dolcetto and Barbera are also grown and provide more affordable, and often delicious, alternatives. Freisa is also an interesting local variety. There also two popular dry white wines produced one from the Arneis grape – at its most characterful in Roero – and Cortese – the grape behind the stalwart white Gavi.

This region is also famous for two semi sparkling (frizzante) sweet wines. These are unique in style and genuinely “fine” in the true wine sense.

- Moscato d’Asti – made from the Muscat grape and cool fermented in a sealed tank, then bottled bottled early under pressure before all the sugar has been fermented

- Brachetto d’Aqui – as above from the red Brachetto grape – both of which are usually produced at low 5.5% abv alcohol

I have picked four lovely mixed examples to try from the region – the classic dry and savoury Gavi de Gavi from the up and coming Estate of Giustiniana. Then two classic reds – a fine example from Barbaresco Roncaglie from Poderi Colla; then an absolute benchmark, refined Barolo from the Vajra family. Then finish with the intoxicatingly delicate Moscato d’Asti from Vajra again.

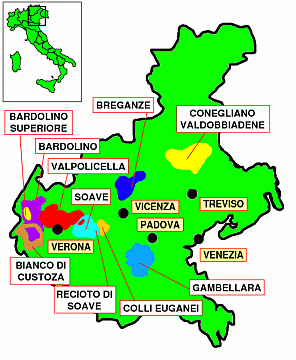

2. Veneto – North East

A famous region with the historic cities of Verona as its centre and Venice on the coast. This is also the production centre for vast quantities of Trebbiano, Pinot Grigio and Prosecco, which is made from the Glera grape. Whereas the vast majority of Italy is mountainous – or at least hilly – this area is really quite flat – and it is on these fertile plains that high cropping vines can be plundered for the more industrial led production wines and price points.

With regards to Prosecco this is made across a vast swathe or vineyards, but there is a delimited higher quality vineyard area near …….. called Conegliano Valdobiaddene. Here the micro climate and soil produce the finest Glera grapes and there is a noticeable increase in quality and concentration. There are no real stand out producers but these wines are generally worth the premium. Within Valdobiaddene there is a special enclave called Cartizze, which is considered to produce the finest Glera and Prosecco of all.

As for still wine the two most important areas and neighbours are Soave (white) and Valpolicella (red). The basis of top quality Soave is the Garganega grape, although Trebbiano is used a lot in blends. With Valpolicella the most important grape is Corvina, but this is often blended with Rondinella and Molinara in differing proportions. In addition, a number of quality producers also rate and use the Oseleta.

Stylistically Soave is a relatively gentle and softly fruity white wine, mainly unoaked and with nutty overtones and medium to medium plus acidity. With age it develops remarkably concentrated honey flavours and can age well for 5 or more years in top examples. Valpolicella is often loosely referred to as “the Beaujolais of Italy” which might relate to its structure rather than flavours, as at its generic table wine level it has low levels of tannin and a soft juicy, cherry fruit character. These wines are made for early drinking and can be very enjoyable.

One of the interesting aspects of these two regions has been how they have used and adapted air drying methods for grapes – a process which is called “Passito” as it creates desiccated shrivelled grapes which are higher in sugar, lower in water content and more concentrated in flavours – and in Valpolicella’s case tannins and increased colour pigments in the grape skins. This process can of course be accentuated with later harvesting dates. Historically grapes were laid out on straw mats and air dried in warm lofts for a number (up to 6 months), then crushed and fermented in the winter. In Valpolicella in particular this process is accelerated via the use of giant air fans, some of which can even be set up to move around the drying trays.

Clearly Soave can also benefit from late harvesting and – even in some years – a touch of botrytis (noble rot). Passito and/or late harvest Soave is a luxuriant sweet wine, more honeyed and waxy with elevated stone fruit character.

Another mixed quartet to finish with – a lovely everyday glugging Prosecco; a benchmark Soave Classico from leading producer Pieropan; a classic cherry fruited, lighter bodied Valpolicella from specialist producer Allegrini, with a nice contrast to the dried grape, richer dry and savoury Amarone style.

Prosecco Extra Dry Cantina Colli Euganei

NA FGWS 2020 10