By Nick Adams, Master of Wine

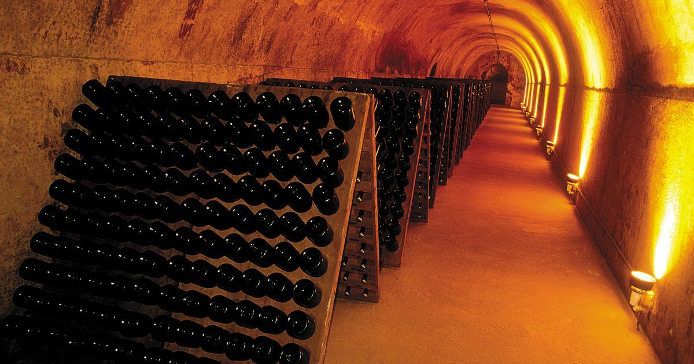

A classic scene of a Champagne cellar where the magic of bubbles happens and the wine ages. It all starts when a solution of dissolved sugar, wine and yeast are added to the base wine blend (as outlined in Part One). This is called the liqueur de tirage in the region and it kicks starts what is referred to as the secondary fermentation. The yeast feeds on the sugar producing a little bit more alcohol but more importantly releases carbon dioxide gas (CO₂). Because the bottle is sealed (usually with a crown cap) the gas cannot escape and physically dissolves into the wine. By the time the yeast has consumed the sugar and died the pressure in the bottle has risen to a remarkably high level – around 6 x higher than atmospheric pressure – or 70-90 pounds per square inch – or 2-3 times greater than that in your car tyre! No wonder the glass is the thickness it is to withstand this force. This part of the process takes from 6-8 weeks. Another interesting aspect of course is that every bottle of Champagne is, in effect, made individually in its own single bottle.

Once the yeast has died it sits in suspension in the Champagne. It now carries out an equally important action despite its ‘mummified’ state. When dead yeast cells remain in contact with the wine they start to decay through the action of enzymes, releasing the cell contents into the wine. Over time this transforms the flavour of the Champagne imparting what is described as a ‘pastry’, ‘biscuity’ or ‘bready’ character both to the bouquet as well as the taste. This process, scientifically, is referred to as autolysis. By law, all Non-Vintage Champagnes must spend at least 15 months in bottle of which 12 months must be on lees. For Vintage Champagnes it is 36 months. Most quality houses and producers leave their NV Champagne on lees for at least 24-36 months. Many believe you must keep lees in contact with the wine that long to impart a true bready or biscuity flavour. And often Vintage cuvées are left longer than 3 years, especially in richer years. Of course, the longer the lees are left in contact with the wine the more exaggerated the flavour and aroma becomes, so the producer needs to be sure that this is what they want for both balance and quality in the wine, but also representative of their house or special cuvée style.

Eventually though the dead yeast needs to be removed – or the Champagne would be cloudy. This is done over time by twisting and turning the bottle gradually upside down to amalgamate the yeast and force it into the neck of the bottle. Historically this (skilled) operation was done by hand, but today this practice is increasingly carried out by software controlled programmes where bottles are group stacked into gyro pallets (please see pictures). This process is called remuage in Champagne (riddling in English). Some houses – such as Pol Roger – still believe in the value of hand remuage, and others such as Louis Roederer retain the practice for their luxury cuvée Cristal.

Once the yeast has been trapped in the neck the wine behind is lovely and clear. It just remains how to get rid of this yeast pellet. The bottles are passed upside down through a very cold heavily saline solution (at around -25°C) for about 2 minutes. This freezes the yeast pellet block in the neck. The bottle is then turned upright, the crown cap knocked off, and the pellet is shot out under pressure. The French term for this process is disgorgement (disgorging).

These days the disgorging is often done in a machine, but this shot (taken at Champagne Krug) shows the effect quite nicely as the pellet pops out when done by hand

The final act in this process is to top up the wine (ie in line with weights and measures) cork and cage it, and apply the long capsule for dressing. The final solution added is a mix of wine and dissolved sugar, called the liqueur d’expédition. The addition of sugar is not to start another ferment as there is no yeast; the use of sugar is to balance the naturally high levels of acid in the finished wine and give it more texture. This part of the final process is called applying the dosage. The shot above shows modern day machinery where the disgorgement and dosage can be done almost simultaneously along with the stopping and dressing of the bottle.

The Champagne cork may come as surprise to you in this form as we more commonly associate it in its ‘mushroom’ shape when opening a bottle. This is the shape and form of a traditional Champagne cork at the point of bottling – you need a strong cork to hold the pressure, supported of course by the wire cage or ‘muzzle’.

Then the capsule. These are from (Louis) Roederer’s sparkling wine Quartet Estate in California. There is a cynic’s story that the origin of these (now seen as part of the elegance of the packaging of sparkling wine) was to hide the great air gap or ullage caused by the disgorgement process in the olden days (when all the processing was done by hand).

This shot shows nicely how the Champagne cork changes shape with bottle age. The one on the right is probably very familiar, the one on the left is how it goes with extended bottle age (maybe 5+ years here). Also, it is the law that all corks must have the word “Champagne” on them, and vintage Champagne must also have the year

Can Champagne Age?

Yes, quite simply, and top examples can age and mature for an exceptionally long time indeed – especially vintage Champagne from a particularly good year. Even a top quality non-vintage will age well for 2 or 3 years if stored well. But you need to like the style as older Champagne takes on notes of mushroom, toast, and honey. Here is the cork from a 1961 vintage Champagne (a great year) opened on its 50th anniversary – and exceptionally good it was (I was told – sadly!).

Champagne labelling

Apart from the obvious pieces of information there are certain terms which indicate the level of “dryness” in the wines which maybe of use or interest. The most common is “Brut”. As indicated in the earlier text the dosage in most cases contains some sugar to counter balance the naturally high level of acid in the wine. To be called “Brut” though there is a maximum level of sugar by law you can apply. Below are the most common terminology indicating levels of sweetness – the sweeter styles are quite rare and mainly used by the houses themselves to accompany desserts and savoury dishes when entertaining.

- Doux more than 50 grams of sugar per litre (noticeably sweet on the palate)

- Demi-Sec 32-50 grams of sugar per litre

- Brut less than 12 grams of sugar per litre – the industry standard dosage

- Extra Brut 0-6 grams of sugar per litre

- “Brut Nature” or “Sans Dosage” contains zero dosage and less than 3 grams sugar per litre (these bone dry Champagnes are traditionally served with shellfish in France)

Santé!

I hope you have enjoyed this pictorially led journey through the world of Champagne. To finish, of course, are 3 Wine Trust recommendations to enjoy – each of a contrasting style. The Ayala Brut Majeur NV is a classic aperitif style, wonderfully delicate, lacy, with bright berry fruit and brioche notes. By contrast the Charles Heidsieck Brut Réserve NV is rich, honeyed, with red berry fruit and choux pastry notes. This is a Champagne which can be enjoyed with food. To finish and a jump into the New World but made by renowned Champagne house of Louis Roederer is the Californian Quartet Estate Brut NV, which is a Chardonnay led blend and a serious challenger to Champagne proper. Lovely stone fruit and pear qualities with a subtle biscuity note.

And Finally…

Want to know what to do with those champagne corks? Here’s some ideas to have fun with!