By Nick Adams, Master of Wine.

It is absolutely fascinating how bottle fermented sparkling wine is made. I could have committed this to prose and included a few pictures but felt that the subject matter in block text might become a tad dry. So, in line with the earlier visual blog on how white and red table wines were made I have reverted to a picture led approach with commentary.

And the focus is firmly on the Champagne (delimited) region and wines – as they were the pioneers in developing the process and are rightly considered to make the finest sparkling wine of all in the world. Anyone else can make sparkling wine and use the traditional bottle fermented process and the same grapes, but they cannot call it ‘Champagne’.

Of course, it all starts in the vineyard with high quality and healthy grapes – here is a lovely shot towards the church in the Premier Cru Chardonnay vineyard of Cuis in the Côte des Blancs district; the leading area for Chardonnay in Champagne.

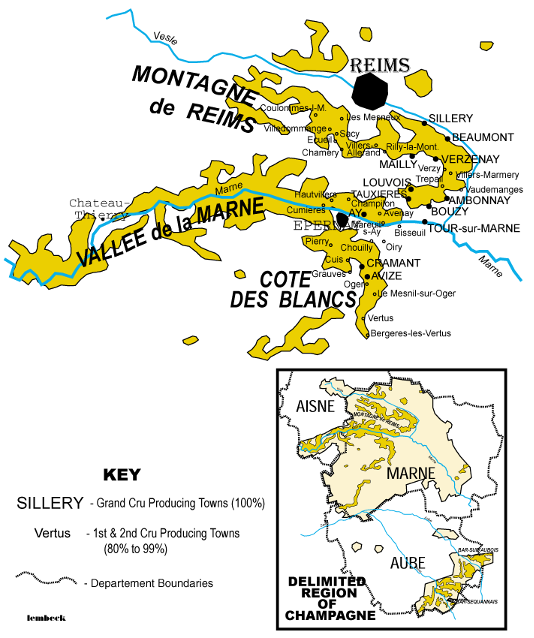

There are 4 main sub regions in Champagne – Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, Côte des Blancs and detached south east of Troyes the Aube. The first three areas contain the finest vineyards. There are over 300 wine producing villages, with the classified best being Grand Cru (just 17 villages!) and marginally less exalted Premier Cru (44 villages). Grapes grown in these top villages unsurprisingly command significantly higher prices. Very importantly too for the vital blending process of the base wine for Champagnes, the same grape grown in one village will taste subtly different when grown in another – what the French refer to as the influences of ‘terroir’.

This is the basket style press that Champagne traditionally uses – many still do – although pneumatic, stainless steel presses are increasingly being preferred. During the pressing, only 2550 litres of juice per 4000 kilograms of grapes are allowed for champagne production by law. The first press is called the tête de cuvée (or head of the cuvée). This press includes the first 2050 litres of juice. The second press is the taille (tail) allowing the next 500 litres of juice. The juice from these 2 pressings is generally processed separately. Top houses and producers in Champagne will only use the first 2050 litres and sell the taille.

Most producers ferment the juice at low temperatures in stainless steel tanks. This creates a very pure and clean wine, seen as a fine basis for the future blending to come. Here is winemaker Didier Gimonnet in the artisan family-owned Blanc des Blancs specialist Champagne Pierre Gimonnet in the Côte des Blancs. A ‘Blanc des Blancs’ Champagne means, by law, that it must be made from 100% Chardonnay. The other two main grapes used in Champagne blends are the black grapes Pinot Noir and (Pinot) Meunier. Chardonnay is the most delicate of the three grapes, so Blanc des Blancs examples are always the lighter bodied and very elegant, but still with tremendous aging capacity. The black grapes – especially Pinot Noir – give real body and power to blends, with Meunier being arguably the fruitiest of the three.

Here is an atmospheric shot taken at Champagne Ayala in the Grand Cru village of Aÿ – pristine stainless steel fermenting vessels and an example of the new wave “Egg” fermenters, also in stainless steel.

However, some Houses also prefer to incorporate wood (not new oak) in their blends as they believe that the gentle oxidation of the juice during fermentation adds a further dimension to the blending components for the house style. This tends to be a practice used by Houses that include a higher proportion of black grapes (particularly Pinot Noir) in their blend, as this grape is best suited to work with wood (as against Chardonnay for example in Champagne). This shot is taken at Champagne Bollinger, firm believers in the importance of the oak component in their Special Cuvée and Grande Année blends. This does not mean all their Champagne is barrel fermented they will use it in partnership with wine fermented in stainless steel.

Réserve Wines

When it comes to blending each Houses’ signature cuvées they will also include a proportion of Réserve wines. Historically these were wines put aside in each (good) year “for a rainy day” – ie a poor vintage – but they are also fundamental to maintaining a consistent, individual and high quality house style. These wines are stored either in large neutral casks or in bottle or magnum in the cellars. And many are from great vintages which have aged magnificently and to levels of great complexity, so a little goes a long way. It is not unusual in top houses for some of the Réserve wines included in the final blend to be well over 20 years old. And therefore, these cuvées must be classified as Non-Vintage, as they are made from grapes harvested in several years. By contrast, Vintage Champagne means a wine in which all the component parts have come from the same single year. These examples are still blends of course – of potentially three grapes from numerous Village sources – but from the same vintage.

It cannot be stressed enough just how critically important the blending of the base wine for Champagne is. The finessing of new vintage wines with older reserve examples, with three different grapes, from xx number of villages, with some wood influenced wine v stainless steel – the conundrum is multi layered. Here are the blending team at Champagne Louis Roederer, led by the highly respected “Chef de Caves” Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon (far right). The objective for this process is quite simple, yet incredibly challenging, to regularly produce a house cuvée which is individual, but consistently individual, and of course high quality.

The other consideration in the blending process at this stage is the production of a Rosé Champagne. Whilst in the rest of the world you can only make rosé wine by law by using black grapes in skin contact with the juice, Champagne is allowed an exception – of course! They are the only area where you can make a rosé by simply adding still red wine to a still white wine (all from the Champagne region to be sure). However, several houses still prefer to make their rosé in the traditional manner with skin and juice contact. This is a shot from Champagne Philipponnat which pictorially shows all options nicely. The one in the middle is the skin contact example; the one to the right is a red wine which could be added to a white wine to create a rosé hue. By the way, the sample on the left says ‘sous bois’ on the label, which means it has been oaked.

Finally, after all the considerations you blend and bottle your still base wine ready for the magical moment of turning it into a sparkling wine. Let’s look at that process in Part 2 of this blog – here we have a white Champagne example, bottled typically at this stage under a crown cap closure.

After reading through this I think you have earned a glass of Champagne!

Why not try our Lallier Grand Cru Grande Réserve Brut, a Grand Cru luxury blend from artisan, family run producer Lallier. 65% Grand Cru Pinot Noir and 35% Grand Cru Chardonnay with 30% of the blend from older reserve wines. Enjoy!