By Nick Adams, Master of Wine.

From its source in Switzerland to its exit into the Mediterranean this monumental river is intertwined with both the physical vineyards and historical importance of not only the wines of The Rhône, but most of France. Although it is not the longest river in France it is arguably the most important. The Rhône was the very gateway by which the Romans brought the vine into France and, from there, introduced it across the country.

Apart from its landscape the most striking aspect of the Rhône is the disparity in size between the Northern part and the Southern. If you were to amalgamate all the main AOC areas in the North, they would only fill about 75% of the area under vine in Châteauneuf-du-Pape alone. The vineyards of the North Rhône are tiny, so production will always be limited and in many cases rare.

In fact, the very imagery of the Rhône could be said to stem from the reputation of one AOC – Hermitage, whose total area under vine is only 142 hectares – incredibly just the same size as one sizeable Château in the Médoc! In 1787 US President Thomas Jefferson proclaimed Hermitage to be “The first wine in the world without a single exception”. In 1828, Hermitage commanded higher prices than any other wine in Europe – including Lafitte (sic), Haut-Brion and Chambertin. Why else would Penfolds originally christen their flagship Shiraz (Syrah) wine as Grange Hermitage?

Maybe due to their size the wines of the North Rhône have never been classified – there are no Grand or Premier Crus to guide the consumer. As a result, much depends on the reputation of producers and their vineyard parcels, which, due to their small size and (ironically well named) reclusive nature, require the drinker to indulge in not insignificant research and learning.

In the South (please refer to previous blog), the commune of Châteauneuf-du-Pape is so dominant (and physically large) that it has become the focal point for consumers and wine writers alike. In between, the North and the South is a wilderness – and a significant distance, during which the whole scenery and climate changes dramatically, from precipitous granite hillsides in a generally continental climate to a flatter, much hotter, truly Mediterranean terrain.

Northern Rhône

In many ways this region starts in Beaujolais, where the limestone mother rock of the main body of Burgundy gives way to decomposed granite in Beaujolais, which then extends on into the Rhône.

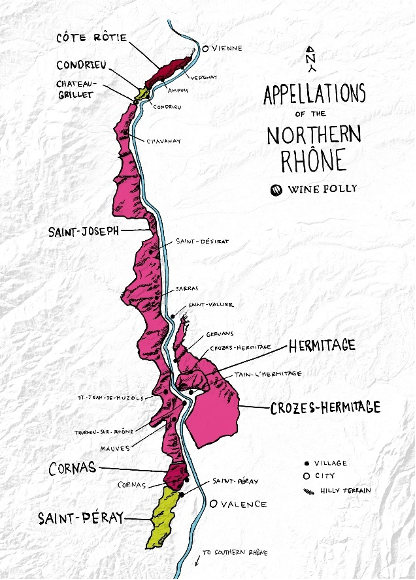

There are 7 main areas – of which 3 are arguably the most famous (Côte-Rôtie, Condrieu & Hermitage) with the remaining 4 being St. Joseph, Crozes Hermitage, Cornas & St.Peray. All the top vineyards are on steep slopes and the majority cling to the river. In theory there are no bad wines here – even the most everyday St. Joseph’s still deliver a certain punch and style. And to make it even easier to grasp all the reds must be made, by law, from the Syrah grape, but with an archaic twist.

About the whites there are 3 potential alternatives depending on where you are. If in Condrieu (and the small AOC enclave of Château Grillet (within it)) you can only make white wine by law and it has to be from Viognier. If you are making white St. Joseph, Crozes Hermitage or Hermitage you cannot make these wines from Viognier, but either/or Marsanne and Roussanne. Finally, there is St. Peray where all wines must be white, including the Rhône’s main sparkling wine area.

The anomaly is in Côte-Rôtie and (historically Hermitage), where producers can add Viognier to their red wine cuvées during fermentation. By law in Côte-Rôtie, up to 20% can be added, but in reality, many only use around 5%, and an increasing number none at all (paradoxically just when it is becoming more fashionable in the New World to add Viognier to Syrah/Shiraz). In Hermitage up to 15% Marsanne/Roussanne can be added to red wine ferments but I know of no producer today that does this.

Côte-Rôtie

Classified in 1940, this incredibly steep, crampon prerequisite, AOC vies with Hermitage as the flagship for the North – and this is down to a large degree to the reputation of one producer – Marcel Guigal. Top wines are plusher and more exuberant than their Hermitage counterparts, but maybe lack its minerality. They are faster maturing than Hermitage and display an opulence which can be very seductive. Today this seems to be the region where several up-and-coming producers (“young turques”) and names are emerging. At their best these are the sexist red wines of the north.

Condrieu

Another 1940 classification, this tiny area is only half the size of Côte-Rôtie. This includes the AOC of Château Grillet (3.5 ha), which is often mistakenly said to be the smallest AOC in France (that honour rests with la Romanée in the Cote de Nuits – 0.85 ha). In summary, this is one of the world’s rarest white wines. So run down did this region become in the 20th Century, that is got close to extinction – but not now. I have never really found out exactly why it became white only, but some producers believe it is due the special soil vein known as “arzelle” which lies in the AOC in the mainly decomposed granite. This artery is made up of fragmented mica, shist as well as granite, with some clay – and the Viognier seem to do especially well here. Certainly, most of the finest wines seem to come from grapes grown on arzelle.

Modern day Condrieu seems to be even richer than ever, with later harvesting, increased use of oak (new barrels) and even some botrytis percentage of grapes included in some blends. The only downside has been the relaxation in yields (ie upwards). These wines are never intended for aging and are best enjoyed with 4 years of release. The key to great Condrieu (Viognier) is that the wines are intensely fruity and perfumed, very full bodied and textural with soft acidity, but never flabby. They can be wonderfully hedonistic.

St. Joseph

The second largest (and most elongated) AOC in the North and an area also dedicated to apple orchards and soft fruit production as well as vines. Both red and white wines are produced – all reds from Syrah and whites from Marsanne and Roussanne. It was formally ratified as an AOC in 1956. Along with Crozes Hermitage, it is the source of the most affordable and relatively ubiquitous north Rhône wines. However, this is an area capable of more than the just workhorse wines with top single examples being very fine. All the best vineyards are not unsurprisingly close (if across the river) to Hermitage in districts such as Mauves and Tournon. These are also the steepest sites and with the poorest soil (a lot of St. Joseph is quite flat). Also, like Côte-Rôtie, there is no town or village called St. Joseph.

Crozes Hermitage

The largest AOC (in terms of vines planted) in the North Rhône – like St. Joseph a good source of more affordable and occasionally great red wines, although the region also produces white wine (again from either/or Marsanne/Roussanne). Registered in 1937 (along with Hermitage) it is split into 5 sub regions – maybe the best being Larnage – these wines at best show all the character of the north Rhône, but less of the intensity of Hermitage, despite their name link. Most of the land is flat, with a heavier clay soil element. Having said this, the best deliver real vitality and freshness aligned to some staying power.

Hermitage

Hermitage was long known and regarded as France’s greatest red, and in the early 19th Century was the most expensive wine in all of France. In this period red Hermitage was regularly shipped to Bordeaux to bolster the frailer reds of the time in that region.

Only about 60% of the size ofCôte-Rôtieand classified in 1937 (ironically the day after Crozes) this is the most famous AOC in the Rhône and, for many, where the greatest – and the Rhône’s most long lived – reds and whites are found. Hermitage also has another trick up its sleeve in that it also produces quite exceptional, if rare and very expensive, Vin de Paille – or sweet dessert wines made from straw dried white grapes. The dramatic, steep granite hill also sits at juxtaposition, being across on the other side of the Rhône from all the other main wine producing areas, apart obviously from Crozes Hermitage. The hill is named after the reclusive (ie hermit) crusader Gaspard de Stérimberg who lived allegedly alone on the hill and built a chapel. Today, a reconstructed white version decorates the top of the hill and is an iconic landmark in the region. The hill dominates the rather dull town of Tain, which is also famous for having the world renowned chocolate factory Valrhona.

A final note about the great white Hermitage – they are really niche and a true wine lovers’ wine. The top cuvées are simply the fullest bodied dry white wines on the planet (beyond Grand Cru white Burgundy for example), but are truly “marmite”. They are either enjoyed young and fresh (ie up to their 5th birthday or then put away for at least another 10 years before opening).

Cornas

Was classified in 1938 and considered by some to be the real home of the “black wines” of the Rhône. Somewhat physically detached from the rest of the AOCs the steep vineyard area is considered to be one of the oldest vine growing areas in France. A sun trap area of the north Rhône – vineyards can be 5°C warmer than Hermitage on the same day – the best sites are found on the steep hill sides, not the overly fertile valley floors. The region is totally devoted to red wine production and only from Syrah grapes. The result is – what might be termed roasted black fruit character – sometimes a tad coarse but always full bodied. The best wines are considered to come from the vineyards behind the (rather plain) village in Reynard and Les Côtes. Soils remain predominantly granite, but here is also a proportion of limestone.

St. Peray

Described by Robert Parker in 1996 as “The Jurassic Park of the Rhône”, this 65ha southerly annex to Cornas failed to set the pulses racing then. It shares one major attribute with Condrieu – it is a white wine only AOC – but this time from Marsanne and Roussanne rather than Viognier. Surprisingly classified before any other Northern Rhône in 1936 it is home to both still and sparkling white wines, although historically outdone by its easterly counterpart Clairette de Die for its Muscat based sparklers. To be fair since those days’ things have moved on and there is increasing interest and development. Recent investment and wines produced bode very well for the future of this “Cinderella” Rhône region.

Wine Trust are in the process of tasting samples for an inclusion from either/or St Joseph and Crozes Hermitage, so please look out for news on that. In the meantime,

Indulge for a treat in the silky, more-ish Côte-Rôtie from the relatively new Domaine François & Fils – a classic example of this AOC and optimising the paucity of production at just 400 case per annum on average. Works beautifully with game or lamb dishes, also char grilled vegetables or a classic ratatouille.