By Nick Adams, Master of Wine.

As part of the occasional series of Blogs under the banner “Off The Beaten Track” I come to one which might just be about in the deepest elephant grass for many wine drinkers – Madeira. And what makes this such a paradox is that – pre Covid – nearly 500,000 UK tourists visited the island each year, so the name and location is familiar.

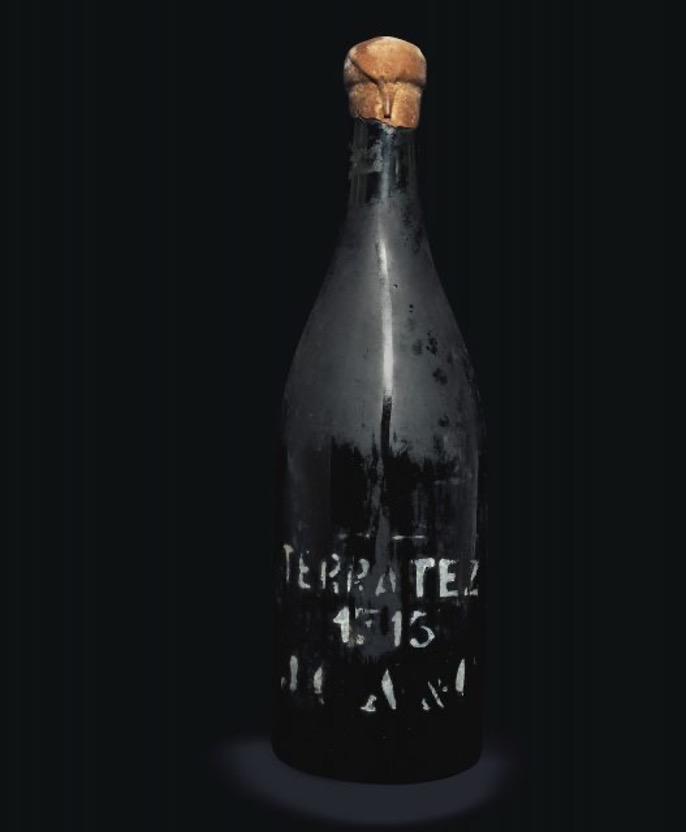

Madeira is quite simply on of the world’s greatest fine wines and one of the oldest vineyard areas and wines in the world. With a history which comfortably exceeds 500 years, Madeira can rightly lay claim to make the longest lived wines of all in the world. In December 2016 Christies sold a bottle of 1715 Terrantez Madeira (so 301 years old) for around £39,000.

A representative of Christie’s auction house, Edwin Vos, had tasted the same wine in 2013, describing it as “remarkably youthful and surprisingly sweet”.

Madeira is a fortified wine made on the Portuguese island off the west coast of North Africa. The history of winemaking is extensive dating back to the 15th Century. The (volcanic origin) island was on an important shipping route for centuries and in the process of shipping the then (fortified) Madeira wine it became cooked, or baked, stored in the hot hull, and arrived in a new style and state. Many took to this style and a shipment arrived back on the island where the producers started the long process of adapting the production process to mimic this (heated) style directly on the island. Over the following decades a unique process was refined which defines the essence of the wine.

Such was the success with the wine that exports soared and by the 18th Century 95% of all production was exported – the main markets being the USA and American colonies, Russia, and the UK. But like the rest of Europe Madeira was hit in the 19thcentury by the twin blight of Oidium and Phylloxera and then in the 20th the Russian and American markets decline significantly. In addition, no one involved in shipping used Madeira as “a port” any longer. However, towards the end of the 20th Century producers became much more quality focused – replanting of superior noble grapes took place – and focused switched very much towards quality production and away from pure bulk and for want of an expression “cooking wine” markets, although these – especially France – remain very important.

The base wine is fermented with the fermentation halted at varying stages to create a range of wines with mixed levels of residual sugar. All Madeiras will have some residual sugar but the range between the “driest” and the sweetest is significant. But it is the aging process that differentiates this wine from all others in the world. The wines are stored in old casks and deliberately exposed to heating over a period. For more basic blends this is accelerated by what is called the estufagem aging process. There are two basic approaches to this outlined below

- Cuba de Calor: This is the most common and used for entry level Madeira. The wine is aged in stainless steel or concrete tanks surrounded by heating coils that allow hot water to circulate around the container. The wine is heated to temperatures up to as 55 °C for a minimum of 90 days as regulated by the Madeira Wine Institute. Most Madeiras these days heat to 46 °C. An interesting adaptation though is the …

- Armazém de Calor: Only used by the Madeira Wine Company, this method involves storing the wine in large wooden casks in a specially designed room outfitted with steam-producing tanks or pipes that heat the room, creating a type of sauna. This process is gentler, and they believe the finer is finer as a result. The process lasts for anything from six months to over a year

However, for all finer, Reserve and Vintage Madeira the more subtle and refined Canteiro process is used

- Canteiro: these wines are aged without the use of any artificial heat, by being stored by the winery in warm rooms – usually lofts – and outside left to age by the heat of the sun. In cases such as vintage Madeira, this can last from 20 years to 50 years. The aging and heating are by definition much slower and less intrusive leading to a more defined and rarefied style

Either way what occurs is that the wine is slowly and deliberately oxidised whilst taking on distinctive cooked or caramelised flavours and aromas. In addition, due to the fact that the wine is fortified and possesses remarkably high levels of acidity the result is that top examples are simply the longest lived wines in the world – frankly almost indestructible!

The island has a warm, maritime climate – which threatens issues with moulds and fungal diseases with the humidity often being high in the growing season. Vineyards are mainly planted on terraces and are often planted on trellises with the canopy raised well above the ground. In the old days this also allowed farmers to crop other (food) crops underneath. Soils are mainly volcanic red and brown basalt. Due to the nature of the terrain machine harvesting is impossible. Today there are around 2,100 grape growers but only around ten or maybe dozen actual producers, of which eight are registered as exporters. The average holding of these growers is very small which explains the small number of producers and exporters.

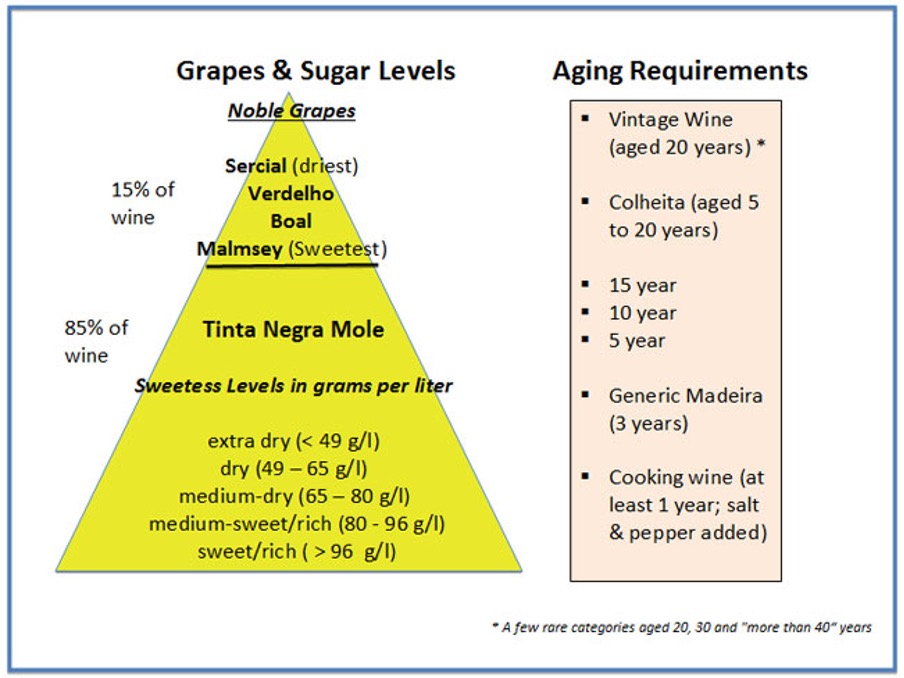

The main grape grown is called Tinta Negra which has been rather unfairly labelled as “workhorse”. Although it accounts for over 75% of overall production, it is more than capable of making high quality Madeira as well as being the source for bulk and cooking styles. There are 4 – possibly 5 “noble” grapes and in order of sweetness in the finished wines, these are:

- Sercial

- Verdelho

- Bual (sometimes spelt Boal)

- Malvasia (also known as Malvazia or Malmsey)

In addition, an ancient variety Terrantez is making a comeback after having been almost totally grubbed up in the 19th and 20thcenturies. Its sweetness level sits between Verdelho and Bual in general.

Even the “driest” style – Sercial – will still have noticeable “off dry” residual sugar on the palate whilst Malvasia/Malmsey is fully sweet.

- Reserve (five years) – This is the minimum amount of aging a wine labelled with one of the noble varieties is permitted to have.

- Special Reserve (10 years) – At this point, the wines are often aged naturally without any artificial heat source.

- Extra Reserve (over 15 years) – This style is rare to produce, with many producers extending the aging to 20 years for a vintage or producing a colheita. It is richer in style than a Special Reserve Madeira.

- Colheita or Harvest – This style includes wines from a single vintage but aged for a shorter period than true Vintage Madeira. The wine can be labelled with a vintage date but includes the word colheita on it. Colheita must be a minimum of five years of age before being bottled and may be bottled any time after that. Effectively, most wineries would drop the word Colheita once bottling a wine at over 19 years of age because it is entitled to be referred to as vintage once it is 20 years of age. At that point, the wine can command a higher price than if it were still to be bottled as Colheita. This differs to Colheita, or “Reserve Tawny” Port which is a minimum of seven years of age before bottling.

- Vintage or Frasqueira – This style must be aged at least 19 years in cask and one year in bottle, therefore cannot be sold until it is at least 20 years of age. The word vintage does not appear on bottles of vintage Madeira because, in Portugal, the word “Vintage” is a trademark belonging to the Port traders!

The terms pale, dark, full, and rich can also be included to describe the wine’s colour.

I would encourage every wine drinker to find time and space in their portfolio to sample and enjoy Madeira. These wines are remarkably individual and refined. And because of their almost indestructible nature can be opened and enjoyed over a long period, making them very good value for money. By that you can open a bottle and it will keep comfortably for over a month – especially when stored in the fridge. It is also an essential element in any kitchen for use in deglazing and making sauces as the umami notes in Madeira have long been revered by chefs and kitchens across the country. It is estimated that 98% of all professional kitchens in the UK stock a bottle of Madeira for these very reasons.

The wine is also versatile with food. Sercial and Verdelho work very well with savoury autumn and winter soups, and Sercial especially so with classic fish bisque soups. These styles also work well with a mixed plate of charcuterie and Tapas style cooking. The richer Bual and Malmsey are a wonderful alternative to have with cheese and work well with any caramelised dish such as stickie toffee pudding or banoffee. And of course, are designed to go with cake – but you can extend this out at Christmas too, including mince pies and Christmas pudding. Or simple enjoy them after dinner in a digestif format.

Henriques & Henriques Malvasia 10 years (50cl Bottle)

Deep amber in colour with a greenish tinge, this is an intense wine with aromas of nuts, honey and wood. Full-bodied and smooth, it has a complex palate of dried fruits, especially raisins, coffee and caramel. Fresh and rich with a long finish.