Sitting in a typical tapas bar on a typically hot evening in Córdoba, I decided to order a glass of Fino – for a change. As a friend and I were travelling around Andalucía, I thought it only right to try the local produce! Plus, it went wonderfully with our selection of dishes, from olives to classic Iberico ham and the assorted shellfish platters. One would be forgiven for thinking it was sherry, but it was in fact its close cousin, Montilla-Moriles, whose vineyards lie south of the city.

Nevertheless, it made a wonderful introduction to the wines of the region, which straddles the entire length of Spain’s southern coast. It also went some way to debunk, admittedly, my prejudices against this style of wine. Though the same distinctive characteristics of sherry are not usually as developed in Montilla-Moriles, the wine was delightfully versatile with delicious trademark nutty flavours. I was thirsty for more.

I never considered myself much of a sherry drinker, but perhaps that was because I hadn’t drunk enough of it! A later visit to the esteemed Bodegas Lustau would suggest otherwise… Maybe it’s time we all reconsider our stance on sherry (if you’re not already a fan) and savour a glass of this often-overlooked Andalucían treasure.

Jerez: where sherry all started

In the southwest of Andalucía not far from the port of Cádiz lies the city of Jerez de la Frontera, or Jerez for short, the historical centre of sherry production. The town is an interesting stopover in itself with a charming old town and the historic 12th century Moorish castle, whilst its bodegas give the excitable tourist plenty of wine tasting opportunities.

Sherry has been produced here and enjoyed by many for centuries, particularly in France, the UK as well as Spain – perhaps unsurprising given their naval activities in and around Cádiz. It was Francis Drake’s sacking of the city in 1587 and subsequent return that popularised the wine back in Britain. The reason the Brits called it “sherry” was they couldn’t say “Jerez” – or “haireth” properly!

The Jerez region was the first in Spain to be given Denominación de Origen status in 1933 and broadly encompasses the towns of Jerez, Puerto de Santa Maria and Sanlucar de Barramenda, in what is known as the ‘Sherry Triangle’.

Only three varieties are grown for making sherry and its various styles: Palomino, Pedro Ximenez and Moscatel (Muscat of Alexandria). The former makes up 95% of total plantings and is the ideal candidate for sherry production, as its relatively neutral flavour profile helps accentuate the iconic characteristics that are developed during the winemaking process.

In the vineyard, plentiful sunshine, heat from eastern plains, and cooling oceanic breezes provide ideal conditions for the grapes to achieve optimal ripeness. This is helped by the famous albariza soil; the albedo effect, as demonstrated by its blinding white appearance in summer, assists the ripening process. These soils also boast high chalk content with excellent water retention, which proves invaluable due to the hot summer months and low annual rainfall.

Lustau: where sherry begins

Walking past the almost fortress like walls of Bodegas Lustau, you wonder what winemakers are keeping so well guarded. Behind lie Lustau’s famous cellars and arguably the most important stage in the production of sherry. It is here, and in cellars all over Jerez, where specific winemaking techniques are employed to produce this special style of wine.

Lustau is a family run enterprise founded in 1896. The winery had modest beginnings, overseen by José Ruiz-Berdejo, a court clerk by day, who cultivated vines on his own land and produced wines on site.

He is what we would call an ‘Almacenista’, an independent, artisanal winemaker who produce small quantities of sherry to sell to ‘shipping’ bodegas further up the supply chain. Lustau is still famous for its Almacenista range, having come full circle from its humble background to its modern day network of wineries that are still at the centre of its sherry production.

Why not try this delicious Oloroso sherry from modern Almacenista, Juan García Jarana?

The winery was relocated and expanded by José’s son in law, Emilio Lustau Ortega, in the 20th century. Soon Lustau began exporting its own Sherries, building its range as well as its reputation. Now part of the Cabellero Group, Lustau has received crucial investment to develop and expand its operations. It has received many accolades, including Best Spanish Producer at the IWSC as well as the IWC’s Best Fortified Winemaker of the Year for its oenologist, Manuel Lozano.

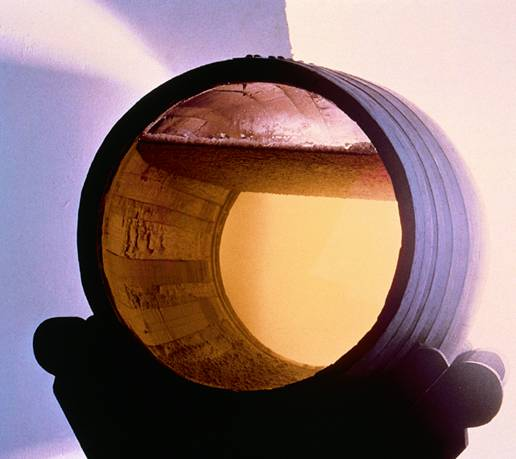

Unsurprisingly, Lustau’s portfolio is vast as it is impressive. Stepping foot into the winery one is confronted with the seemingly endless rows of barrels; these are all part of the solera ageing system, which is a crucial mechanism in the production of sherry.

It consists of three levels, the second criadera, the first criadera and the solera from top to bottom. The latter represents the final stage in the maturation process, before which new wine is passed through the top level, blended with various vintages on the way down in a particular order.

By law sherry must be at least 3 years old, but in practice it is often aged for much longer through many secret ageing recipes! This fine tuned system of blending is crucial for developing and maintaining the house style.

There is certainly more to the solera system than meets the eye, and if one were able to see through the barrels they would witness another very important process. This essential part of production is what is known as the flor a blanket of yeast that forms over the top of the wine in barrel. The barrels are deliberately left with an air pocket in the top, which allows indigenous yeast to develop, as seen below:

The flor’s protective layer stops the wine from oxidising, although as we will see this is sometimes desired depending on the style of sherry being made. It has many other important roles, including the production of the compound acetaldehyde, with imparts that distinctive nutty flavour.

All Sherries that develop this Flor “duvet” are immediately classified as Fino Sherry. Fino is the driest and most delicate style of sherry, which exhibits characteristic nutty, tangy and saline flavours.

As does Manzanilla, a specific style of Fino that is only produced in Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Its coastal location means it is typically more humid, which allows an even thicker flor layer to develop. As a result, it is even more delicate than Finos produced inland. One also picks up camomile notes, as the name Manzanilla suggests, and prominent saline qualities. I was luckily enough to be given a tasting, and the difference between two styles immediately stood out – this does demonstrate the importance of geography!

Next come the oxidative styles of sherry, produced in the absence, or very low levels, of flor. The colour of the wine immediately gives it away, displaying amber or brown hues. The process of oxidative – or envejecimiento – ageing is another crucial element in the production of sherry. The wine interacts with the air and begins to develop richer and more complex flavours, such as the signature toffeed, dried fruit and roasted nut notes.

Palo Cortado is the first of these styles; it is a rare example and occupies a sort of grey area when it comes to sherry classification. Originally, it started life as a Fino where the flor has failed to develop normally, for various reasons. The wine is then taken out of the Fino solera, fortified and aged separately. Nonetheless, it is interesting to detect the richer, complex flavours brought about by oxidative ageing.

Next comes Amontillado – a term that actually originated from the Montilla region mentioned earlier. This is a sherry that develops a flor but continues to be aged once this is lost.

Finally, Oloroso sherry is aged entirely without the flor layer. The base wine is selected then fortified to stop the development of indigenous yeast, then aged oxidatively over many years. Oloroso means fragrant in Spanish and these sherries do display fabulous, multi-layered aromas that translate into a long, complex palate.

Try one of our favourite Olorosos from Lustau, this wonderful Pata de Gallina

Finally, we come to the sweeter styles of sherry, produced with the Pedro Ximénez or Moscatel grapes. You can also get sweetened Oloroso, with the addition of PX or leaving some residual sugar in the base wine. Oloroso styles of sherry that have been sweetened are known as Cream, named after the once popular Bristol Cream sherry by Bodegas Harveys.

Whilst many are turning away from cream sherry in favour of drier styles, the sweeter sherries offer a luscious, hedonistic treat. Because of the climate, these grapes achieve remarkable levels of ripeness and are often dried in the sun to concentrate flavours. Pedro Ximénez, the sweetest style of all, is a remarkable wine, viscous and packed full of rich, intense flavours of fig, toffee, chocolate, coffee and soft spice. A liquid dessert in its own right!

Try our Pedro Ximénez ice cold or served over vanilla ice-cream for a real tasting experience.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time at Lustau and left with a newfound appreciation for this unique and remarkable wine. The versatility, complexity and variety to come out of this small corner of Andalucía is something to be admired, something born out of centuries of tradition, innovation and collaboration between bodegas big and small across Jerez and the surrounding area.

Sherry is something I grew to love during my time in Spain and ended up growing quite an appetite for! I was particular fond of the Pedro Ximénez, a fantastic end to any tapas meal (of which there were plenty). After seeing all the history and hard work behind sherry production, it is something I vowed to try more of. Perhaps if you’ve made it to the end of this piece, it is something we can all agree on!