Part One – The Harvest and Red Winemaking (prior to aging)

It all starts with grapes on the vine: and it is important that these are both healthy (no rot) and properly ripe. Not ripe enough, or too ripe, and the wine will suffer. The grapes contain all the potential of the wine: you can make a bad wine from good grapes, but not a good wine from bad grapes. Harvest takes place in the autumn – September to November Northern Hemisphere, March to May Southern Hemisphere.

Ideally, there should be just the right balance of sugar and acid, as well as “tasting” good when sampled. For black grapes, the tannins in the skins also need to be “ripe”. Winemakers will test a sample of grapes in the laboratory prior to agreeing the harvest date with the vineyard manager (and subject to prevailing weather conditions of course).

Teams of pickers head into the vineyard. This is an exciting time of year, and all wine growers hope for good weather conditions during harvest. Bad weather can ruin things.

Hand-picked grapes being loaded into a half-ton bin.

Increasingly, grapes are being machine harvested. This is more cost-effective, and in warm regions quality can be preserved by picking at night, when it is cooler. This is much easier to do by machine. But the terrain needs to be right – you cannot do this on the side of a steep hill!

The harvester shakes the grape berries off the vine and then dumps them into bins to go to the winery. This shot is taken in Bordeaux.

These are machine harvested grapes being sorted for quality (and removing debris and spoiled grapes)

Hand-picked grapes arriving as whole bunches in the winery.

Sorting hand-picked grapes for quality. Any rotten or raisined grapes, along with leaves and stalks, are removed.

These sorted grapes go to a machine – called the “destemmer” – which not unsurprisingly removes the stems. The berries may also be crushed, either just a little, or completely.

These are the stems that the grapes have been separated from in the destemmer. These can then be composted and put back into the vineyard as fertiliser.

Reception area at a small winery. Here black grapes destined to make red wine are being loaded and then taken by conveyor belt to a tank, from where they are being pumped into the fermentation vessel.

When you squeeze a wine grape the juice that runs out is water white in colour – whether the grape you use is black or white. This is because the entire colour is contained in the skins of (black) grapes. Therefore, if you want to make a red wine you must keep the juice and skins in contact with each other. In a simple analogy, it is like making a giant pot of tea where contact between the water and tea leaves produces both the flavour and colour of the beverage.

This is where red wine making differs from whites. Red wines are fermented on their skins, while white wines are pressed, separating juice from skins, before fermentation. This fermentation vessel – a shallow stone lagar in Portugal’s Douro region – will be filled up and then the grapes will be foot trodden, so that the juice can extract colour and other components from the skins.

This is a very traditional method in the Douro (and still used by a number of Port houses for their top vintage ports – eg the sublime Taylors Quinta de Vargellas Vintage Port.

The red grapes have been foot trodden, and fermentation has begun naturally. These men are mixing up the skins and juice by hand: this process is carried out many times a day to help with extraction, and also to stop bacteria from growing on the cap of grape skins that naturally would float to the surface.

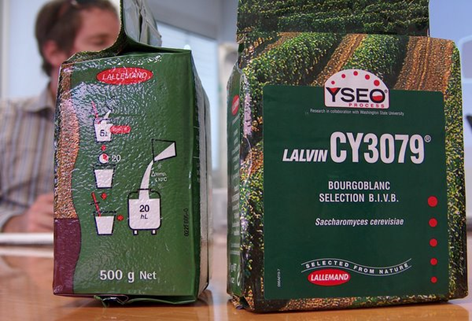

Sometimes cultured yeasts (Saccharomyces) are added in dried form, to give the winemaker more control over the fermentation process. But many fermentations are still carried out with wild yeasts, naturally present in the vineyard or winery, or the skins of grapes (called “bloom”). Anyone making Organic or Biodynamic wine will always use natural yeasts as part of the expression of the vineyard in the wine.

These black grapes are being fermented in a “open” stainless-steel tank. During fermentation, carbon dioxide is released, a proportion of which escapes in an open top fermenter. The gas also pushes up the “cap” of skins, so you need to ensure the skins are kept in circulation with the fermenting juice to extract colour (and tannins). Sometimes, however, fermentation takes place in closed tanks with a vent to let the carbon dioxide escape.

In this small tank the cap of skins is being punched down using a robotic cap plunger. In some wineries this is done by hand, using poles. In Burgundy, this process is called Pigéage.

A classic example of a wine made this way is the excellent Lawson’s Dry Hills Reserve Pinot Noir from Marlborough New Zealand – made in a truly artisan manner by winemaker Marcus Wright

An alternative to punch downs is to pump wine from the bottom of the tank back over the skins.

Here, fermenting red wine is being pumped out of the tank, and then pumped back in again. The idea is to introduce oxygen in the wine to help the yeasts in their growth. At other stages in winemaking care is taken to protect wine from oxygen, but at this stage it is beneficial in controlled amounts.