By Nick Adams, Master of Wine.

It is estimated that 90% of all wines produced are made, bottled, and consumed within 2 years. Here the value of the wines’ styles is all about freshness and fruit and immediate (primary) flavours and pleasure. For a relative handful of wines, the opposite is true – these examples either demand aging (for practical purposes) or are simply much better wines for a period of maturation.

There are also important other aspects – wines from certain years may be bought to mark a birth year, anniversary, or special event – and to be opened on a suitable celebratory occasion (like an 18th birthday).

And some wines are just made, blended, and aged as part of their very quality and style, so when the consumer purchases them, they are already matured examples. These wines have what is termed as tertiary flavours and aromas rather than primary as with the young newly released examples. And of course, a major prerequisite is that for any wine to age and improve it must have been well made in the first place. And yes, you must also enjoy the style and flavours of an older, matured example which is a very personal choice.

And in some cases – Champagne is a good example – you can enjoy them just as well as a younger, new released example or with extended bottle age – they are both Champagne but will taste and smell quite different.

So, let’s look at what happens to wine as it ages and matures and select some prime examples from the Wine Trust portfolio which reflect these characteristics.

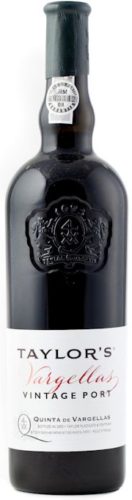

The key elements (apart obviously from the fruit concentration levels) in wine which allow it to age (and improve) include acids, alcohol, sugar and (in reds) tannins. So, a wine with high(er) levels of these components has the potential to age for a considerable time – maybe the most famous example is Vintage Port.

As a wine ages the nature of the acidity will change. This is due to the esterification of the acids, combining with the alcohol to produce esters. These esters can be attractive in both smell and flavour. Another important aspect is the environment the wine ages in – by that in a cask (oak barrel) or in a bottle (or both) over time. When there is greater exposure to oxygen (ie in a cask) the faster wine will evolve and more “oxidative” it will become. An example of this is with aged sherry such as Amontillado or Oloroso where alcohols are oxidised to produce compounds such as aldehydes which are highly aromatic. With some wines – most famously Madeira – the production and aging process is so (deliberately) oxidative that the wine’s intrinsic character is therefore oxidative, and with this incredibly stable and long lasting as a wine. Examples of 19th century Madeira can still drink incredibly well for example.

In the inside of a bottle the environment is much more “reduced” (with no or very little oxygen) so the aging process is slowed down considerably but the potential for more complex and delicate aromas and flavours is enhanced. In fact (through gas chromatography) scientists have identified over 800 different chemical components (obviously in tiny amounts) in bottle aged wine!

With red wines the role of tannins is particularly important – these are strong antioxidants so whether in cask or bottle they act as a buffer to the intrusive nature of oxygen slowing down the aging process to help create more complex aromas and flavours over time. In addition, as the tannins themselves slowly oxidise they become “softer” in texture and eventually will fall out of solution as sediment – hence the need to decant these wines (again most famously with Vintage Port).

As wine ages its colour changes significantly. For both whites and reds, the wine becomes browner over time. If the wine has been aged in an oxidative environment this will be exaggerated (please see the Wine Folly ® picture of a young Pinot Grigio (made in a completely non oxidative process) versus and a cask aged Oloroso sherry of around 12 years of age).

With red wine a youthful example will have deep ruby and purple colours. With age the intensity reduces, and browner (eventually tawny) colours develop. Again, please look at the very good Wine Folly ® picture which illustrates this.

However, it must be stressed that aging wine for aging sake may not guarantee any improvement. In some cases – and this has been a criticism of some New World wines – the wines age and keep well, but do not necessarily change or “improve”. They just “freeze dry” for want of an expression. And you can over keep a (good) wine and find that when you open it the aroma and flavours are just too oxidised, the fruit is dead, and maybe it is even faulty. I have had this experience sadly when have kept a wine too long and wished I had opened it earlier! And, of course, the storage conditions are vitally important.

Traditionally an underground cellar was the ideal environment with a constant cool temperature and element of humidity. But this is not always available, affordable, or practical. Other options include investing in a proper wine fridge. With a constant 12-14°C environment, these really are worth the investment if you have a collection of fine and/or special bottles you wish to keep for an extended period.

More expensive, but certainly impressive, are the “walk down” cellars cut into a floor in your garage or kitchen/utility area. These are ideal storage areas (and can be used as a pantry too) but you need to understand important aspects such as the water table level in your area before embarking on excavation – let alone the cost.

And there is also much debate whether a bottle which has a natural cork closure will age better than one under screw cap. This is extremely hard to measure accurately although several producers (mainly in the New World) are bottling some top wines under both cork and screw cap and monitoring how they age overtime when stored in identical conditions.

And, very importantly, is the quality of the vintage itself. Clearly, the better the vintage conditions and year the greater capacity for the wine to age and improve both longer and to a higher level. Conversely a poorer/weaker vintage means drink up earlier.

In addition, larger format sizes – eg a 150cl magnum – are the ideal size for prolonged aging as the ratio of wine to (potential) oxygen contact is much reduced.

Examples of aging in specific wines

As said liking the style of an older wine is very much a personal matter. To give you a few practical examples below – subject to good storage and vintage as mentioned:

- Young v Aged Champagne

Champagne is an interesting example in that most top houses non-vintage Champagnes already have significant aging – including a proportion of reserve wines which could over 10 years old and then 3 years bottle aging on lees prior to release. But in essence a new release Champagne will be crisper, with apple, stone fruits and/or red berries with a bright toasty, brioche character. Older mature examples will be more golden in colour, less overtly fruity, the toasty character will be more exaggerated, and notes of mushroom and honey could have well evolved.

- Young v Aged Pinot Noir

Apart from the colour change the flavour and aromas profiles change from bright cherry and red berry fruits, with a touch of cinnamon to earthier notes (sous bois), some mushroom and a savoury/umami fruit and flavour profile.

General aging properties of some selected wines which have the capacity to mature and improve (from release) – will vary by quality of vintage and style of individual producer of course

Again, subject to vintage and storage the following are hopefully a good guideline:

- Bordeaux Cru Classé (red) – 10-50 years

- Bordeaux top Sauternes – 10-25 years

- Burgundy Grand Cru Red – 10-25 years

- Burgundy Grand Cru White – 5-10 years

- Châteauneuf-du-Pape Red – 8-15 years

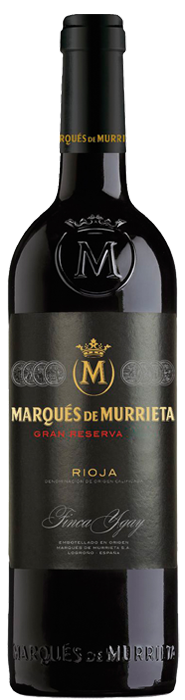

- Gran Reserva Rioja – 5-20 years (another good example of a wine which is released already with considerable aging. By law, all Gran Reserva Rioja must be at least 5 years old (mix of cask and bottle) prior to release – hence the colour change too versus a younger wine

- Barolo/Barbaresco – 5-15 years

- Champagne NV – 2-5 years

- Champagne Vintage 5-30 years

- Top German Rieslings 5-30 years

- Top Australian Shiraz 5-20 years

- Top New World Bordeaux Blends 5-20 years

- Vintage Port 15-50 years

Champagne Charles Heidsieck Brut Réserve NV – aged for over 3 years prior to release and with reserve wines of an average age of 10 years this is classic example of a more mature Champagne (upon release) but also one which can be aged for up to another 5 years for a more honeyed and savoury character.

Marqués de Murrieta Gran Reserva Rioja 2012 – aged for 6 years prior to release (in a mix between US oak casks and in bottle) from their top Ygay single vineyard. Raised in an oxidative environment this powerful wine has such fruit intensity, measured oak and structure that it will age and improve for at least another 10 years, gaining greater savoury and umami notes without any loss of fruit flavours

Taylor Quinta de Vargellas 2002 Vintage Port – from Taylor’s leading single vineyard, by law Vintage Port proper must be bottled after 2 years in cask, so an example of wine which ages away from oxygen in the bottle. Already approaching its 20th birthday this is ready to decant and drink now but will continue to age and improve for up to another 10 years should you wish (ideal as a nice treat for a 21st birthday in 2023, or a 25th anniversary in 2027?)