By Nick Adams, Master of Wine.

The recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s new report (summary) has sent reverberations around the world and set politicians and scientists into an understandable frenzy. For weeks now details have been well publicised of the excessive and unprecedented temperatures in both the Western USA and Canada. And just recently Italy (Sicily) recorded the highest ever temperature in Europe at 48.8°C. We have also seen too many images, for comfort, of torrential rains and flooding, wildfires, along with ice shields melting and warnings of rising sea levels. Apart from the general distress and devastation for people, communities, and commerce it creates a sense of foreboding for the near, let alone long term, future. And the wine trade – and above all those growing grapes and making wine – is/are slap bang in the middle of this situation.

The highest (shade) temperature I have ever personally “enjoyed” was some years ago in California when we hit 50.1°C in the shade one afternoon – quite an experience for an Englishman abroad. Of course, this was just temporary as we soon were inside in perfectly air-conditioned offices after being out in the winery and vineyards, but it was quite a shock at the time to think that these sorts of temperatures were possible.

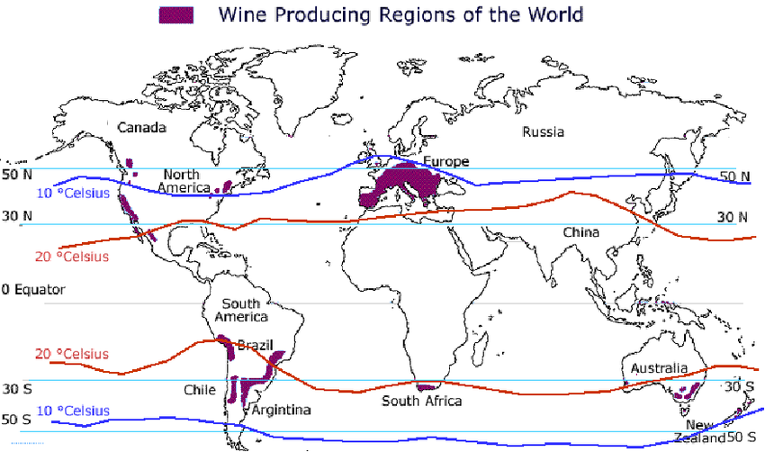

The historically accepted world map of ideal wine growing conditions has long said that the best and most consistent conditions are found between 30-50 latitude north and south of the equator (please see map). But with climate change is that all set to change?

The ideal growing conditions for a vine are historically found in these bands – not least in that minimum summer temperatures (by that consistently above 20°C each day) allow the grapes to form, develop and above all ripen to allow consistently commercially viable crops to be harvested. Ideal growing conditions include the concept of “diurnal range”. By this the high: low temperature range that a vine experiences each day and night over the growing season. The best wines are made where the diurnal range is broad – by that the warm days are offset by cool nights. The warm days are vital of course to ripen the grapes and create sugars and flavours; but equally the cool nights allow the vine to “relax” whilst respiring, maintaining important levels of acidity, and reducing vine stress overall.

The problems begin when things turn excessive. Above 35°C the vine and grapes will start to become increasingly stressed. Above 40°C and it can get serious. Of course, there can be mitigating factors -such as canopy shade to protect the grapes from sun burn and (in the New World) irrigation systems to keep the plant hydrated. Paradoxically in the Old World (ie Europe) irrigation is broadly outlawed so growers have to petition for a licence to use this system in extreme summers, such as in 2003 to take one example. In these instances, there is often a serious level of vine mortality before the irrigation is authorised.

Even if the vine survives when it becomes too hot the plant simply shuts down (to survive) – water and sugars are reversed away from the grapes to the trunk and root system for it to remain hydrated. Despite very warm temperatures the grapes fail to ripen and start to desiccate into raisins. Chlorophyll levels drop, and eventually the crop is ruined even if the plant survives the assault. In addition, the vine may be weakened overall so the next growing season’s production can also be badly affected, even if that year’s temperatures as more moderate.

And with global warming this is only set to exacerbate. But is it all bad news for all growers?

Ironically some growers may benefit as they move from highly marginal climates to warmer (not hot, hot) and more consistent growing conditions – and this potentially includes England. A Burgundy producer based in Beaune recently told me that the effect of global warming has meant that his coolest sites on the northern edge of the Appellation are now ripening much earlier and more consistently than he ever remembers (and his experience in Beaune goes back some 25 years) – and every year Pinot Noir grapes are being harvested with increasing levels of ripeness, sugar, and flavour. But for others the converse is more worrying.

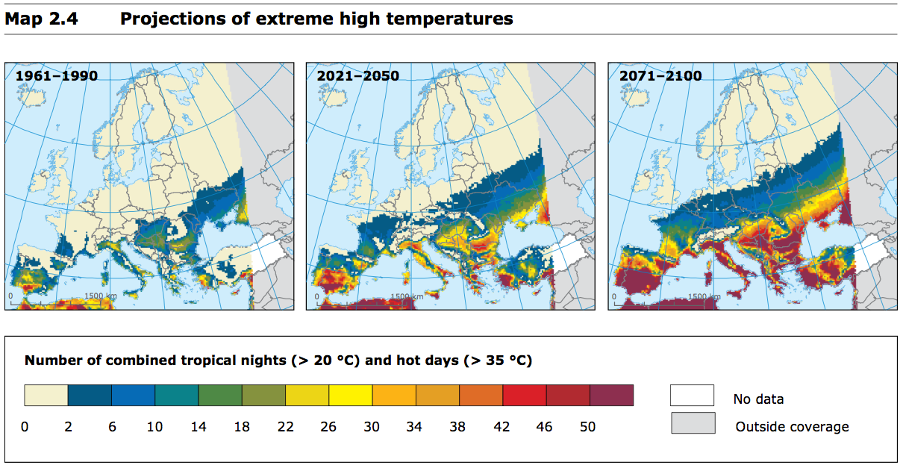

If you look at the projected weather and temperature chart (below) for Europe over the next 80 years, there is unprecedented evidence that areas once defined as “moderate” will become continental and those termed marginal will become moderate in vine growing terms. But those already defined as continental may simply become too hot to grow grapes that make a quality and above all balanced wine. And the problem for our friend in Beaune is that varieties like Pinot Noir are highly susceptible to temperature rises – by that they only make good wine in marginal and moderate climates anyway.

The problem for the New World may potentially be even more serious. The New World – which is predominantly defined as all countries in the Southern Hemisphere plus North America – are already significantly warmer on average than the Old World. This is partly down in the southern hemisphere to the fact that the Ozone layer is thinner so Ultraviolet light intensity is stronger – and this aspect is not solely dependent on temperature either. Average summer temperatures can easily be up to 5°C greater than in their European counterparts. As a result, the grapes simply get riper all things being equal. We all know from drinking New World wine how much juicier, or riper, and fuller bodied the wines from these countries can be versus their counterpart styles and grapes grown in the Old World. This may not be a bad thing if you like that style of course and does not mean they are inferior. You, as a drinker, may prefer these over the leaner and higher acid counterpart examples in the Old World. However, if the Ozone layer thins further and temperatures rise anyway these wines may become, in general, increasingly higher in alcohol and more unbalanced.

But it is not all gloom and doom of course – there is still time for mankind to refocus efforts to moderate the worst excesses of climate change and growers will adapt so that areas once deemed unsuitable for the consistent growing and harvesting of grapes become commercially viable. Existing producers may adapt – if laws allow – and start planting varieties which enjoy and do better in warmer climates. Marc Perrin, one of the co-owners of Château de Beaucastel, in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, told me that a) global warming had unquestionably affected their vineyards, growing seasons and harvesting regimes and b) that even Grenache was starting to struggle some years with the heat, but Mourvèdre (a vital part of the Beaucastel blend) adapted much better to higher temperatures, so its proportion in the blend may well increase in the coming years.

An interesting and very practical example, but this issue also comes with a threat to tradition, a producer’s established style, typicity and the whole concept of what the French term terroir. Only time will tell, but one thing is for certain – vine growing and winemaking are set to change.

Let’s finish though with a nice cross reference example of a white and red made in the Old World and New World to see the style and origin differences when still using the same grape and processes. I love this sort of tasting comparison which when it works showcases how good both Old World and New World wines can be when based on the same model.

Chardonnay & Pinot Noir – both from Burgundy and cooler climate Australia – both made to the Burgundian model

A nice pair Alain Chavy is one of the leading winemakers in Puligny Montrachet and the grapes used here are sourced from just outside the Puligny appellation. The M3 Chardonnay is made by leading Adelaide Hills producer Shaw & Smith. Both are barrel fermented but with the emphasis very much on balance, texture, and poise.

Shaw + Smith, ‘M3’ Adelaide Hills Chardonnay

Vintage: 2018, Order as: single bottle

And now examples of Burgundy’s other great grape Pinot Noir – one made by the completely rejuvenated and on top form Burgundy house of Château de Santenay, and the other, again cooler climate Tasmanian, made by Devil’s Corner – both made to the red Burgundy model.

Château de Santenay, Mercurey Rouge ‘Vielles Vignes’

Order as: single bottle