Following on from the Burgundy blog I thought it might be interesting – as indicated in that blog – to look at Chardonnay more broadly – ie above and beyond its role in Burgundy – as it crops up more than you might think. Whether you are the most avid fan of White Burgundy, or the most cynical “ABC” (anything but Chardonnay) drinker, there is no escaping the fact that, commercially, Chardonnay remains the most important white variety in the world. And to contrast Burgundy the focus will be on fine examples of Chardonnay from the New World, with twist back to France.

It is the second most widely planted white variety in the world and one the most adaptable vines for wherever it is grown. From the coolest, marginal to the warmest (micro)climate Chardonnay can produce wines of good to world class quality and in dramatic range of styles.

Chardonnay Vine

The variety itself is quite hardy and buds and ripens relatively early. This aspect is very important in cooler sites and regions. Though very vigorous is not naturally a heavy cropper (say in relation to Sauvignon Blanc) which assists in providing the levels of concentration and power for which it is rightly renowned. Not the most aromatic of varieties (say again versus Sauvignon or Riesling) what are the flavour profiles of this grape?

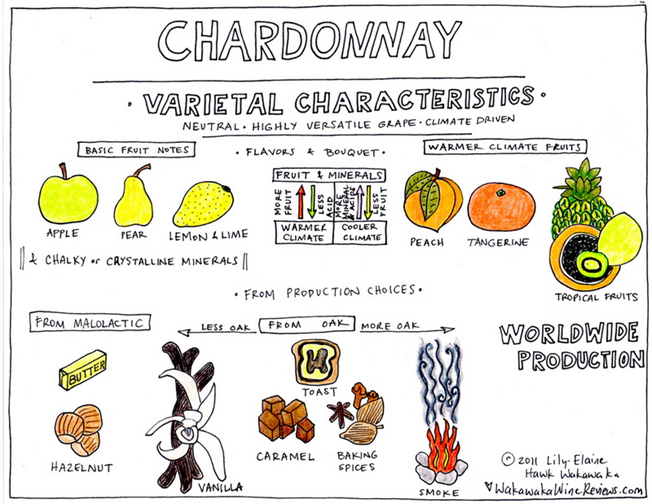

The range of smells and flavours associated with Chardonnay

Cool climate Chardonnay has aroma and flavour notes of apple, mildly citrus and white stone fruits. As the climate becomes more moderate the intensity of the stone fruit character becomes much more intense – almost “peachy” in certain areas. In warm growing areas tropical notes emerge of melon, pineapple, even mango alongside the stone fruits.

As discussed in the Burgundy blog, one of the major differences for Chardonnay (v most other white wines) is that its production process is often the most manipulated. Whereas most fruity and aromatic whites are cool fermented, unoaked and bottled early, many Chardonnay go in a diametrically opposite way. The norm for most of the quality and artisan Chardonnay wines is to make and model on the traditional heartland methods devised and fine-tuned over generations in Burgundy.

These include barrel fermenting the wine at a higher temperature than in inert stainless steel. This not only imparts oaky, toasty, or vanilla notes but builds on Chardonnay’s already inherent richness and body to make a much more textural wine. In addition, the wine is then aged for an extended period on the dead yeast cells, called the lees – often with stirring of the wine in barrel – to add subtle bready notes.

The “lees” having been stirred in a barrel of Chardonnay!

Finally, the vast majority also go through a secondary fermentation process called the malolactic. Here bacteria feed on part of the malic acid in the wine (one of the main acids in wine) and convert this into a much softer acid – lactic. This is also the acid found in many dairy products. In addition, biproducts such as diacetylare produced. This component has an intense buttery flavour, so along with lactic an overall “buttery” character is created. This process can also create some attractive nutty notes. Add this to the oak and yeast elements and the wine becomes even more complex and textural.

Of course, you can still find unoaked Chardonnay – most famously in Village level Chablis in Burgundy– but here again lees aging and malolactic will still occur. So, outside of Burgundy, let us look at some representative and top examples of this grape from around the New World and how their styles may be changing. And, of course, some drinking recommendations from the Wine Trust list.

One of the best aspects about so many of today’s “new wave”, New World wines is how much more “cool climate” and balanced they have become in recent times – with less emphasis on fatness in the wine and heavily toasted oak styles – and with more pristine fruit qualities. Some ten years ago my heart would sink at the prospect of an Australian Chardonnay with their (too often) booming alcohol, pineapple chunks and bitter oak character – but not anymore! It really does seem that the heavy, alcoholic and over the top oaky styles of Chardonnay have gone.

This is because good producers in these countries have planted more Chardonnay in selected cooler sites – using aspects such as altitude and cooling (sea) breezes. They have also looked to pick earlier when sugar levels are relatively lower (and therefore potential alcohol) and acidity remains higher. Then the use of oak has become much more subtle with less time spent in wood and casks which are more lightly toasted. Then working assiduously to the Burgundy production model, they are creating wines of which many have a genuinely “classical” feel to them.

Some top regions in the New World include Carneros and Sonoma in California, Hemel-en-Aarde and Elgin (Walker Bay) in South Africa, Adelaide Hills, Margaret River and Yarra Valley in Australia, Central Otago and Marlborough in New Zealand, and Casablanca and Leyda Valleys in Chile.

And below are 3 excellent examples of the modern face of Chardonnay in the New World. The Casas del Bosque offers really great value for money, whilst both the Newton Johnson and Shaw & Smith M3 capture the very best of both South Africa and Australia.

Maybe the slight surprise is that very little Chardonnay is found in the rest of Europe outside of France. Pockets exist in Italy and Spain, but these are relatively limited, or local, or the passion of a few individuals in the mix of their portfolio.

A Twist in the Tale

One final aspect of Chardonnay though worth highlighting is its part in producing some of the world’s finest sparkling wines. It is a key component in many of the highest quality Champagnes – often blended with Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. It can also be the lead, star role, in the Champagne style called Blanc de Blancs, which are required to be made from 100% Chardonnay. These Champagnes are the epitome of delicacy, finesse and elegance and showcase as well as any wine in the world just how refined a grape variety Chardonnay is. The finest of all these Champagnes are found in the region called the Côte des Blancs to the south of Epérnay. Here deep, chalky soils provide the ideal environment for the grape to produce wines which are simply mesmerising – so much so that top Villages in this area – such as Cramant, Avize, Mesnil and Oger are accorded Grand Cru status. The Le Mesnil Grand Cru example below – from the local Co-operative – epitomises the refined and delicate style of Chardonnay as a single signature in a Blanc des Blancs Champagne.

Overall, I feel most Chardonnays made today – and at all levels – are as good as they have ever been. As importantly, I think they are made in a better balanced and more refined way. It may be time – if you fell out of love with this grape – to relook at this variety.

Chardonnay and Food

Chardonnays which have been barrel fermented and aged are predominantly designed to go with food. They are natural partners with most fish dishes – especially if served with a butter-based sauce. Any rich, or roasted vegetable dishes also partner well with this style of Chardonnay. And of course, any general white(r) meats – such as chicken or pork will work comfortably too.

Crisp, dry unoaked Chardonnays and Blanc des Blancs can be enjoyed as an aperitif, but make excellent partners with canapés, shellfish and sushi.