By Nick Adams, Master of wine

INTRODUCTION

The wines of Bordeaux have held a special place in the hearts of many generations of British wine drinkers – generating some remarkable levels of loyalty and imagery. For many this region is seen as the epitome of fine wine drinking, but these days the top wines that have built and sustained that reputation and imagery have reached, in many cases, simply eye watering prices – making them the preserve of the rich, or the investment tool of the wealthy speculator. In my lifetime alone I have seen many estates price themselves out of reach and this has created what might be described as a multi-tiered market all held under the banner of brand “Bordeaux”.

It is still possible to buy a bottle of “Bordeaux” – mainly dry white – at comfortably under £10, whilst at the other end of the scale top estates and “Châteaux” are often sold on allocation only, and comfortably exceed hundreds of pounds a bottle. However, there are still finer more affordable examples to be found but it requires some serious sieving and investigation – which I hope to help you with over the next two blogs!

In this first part I will look at the background to the region, the geography and climate and the famous (or infamous!?) classifications. In part two will look at the grape varieties and regions behind the wines, with some highlights in the way the wines are made. There will be recommendations along the way from the Wine Trust list of course.

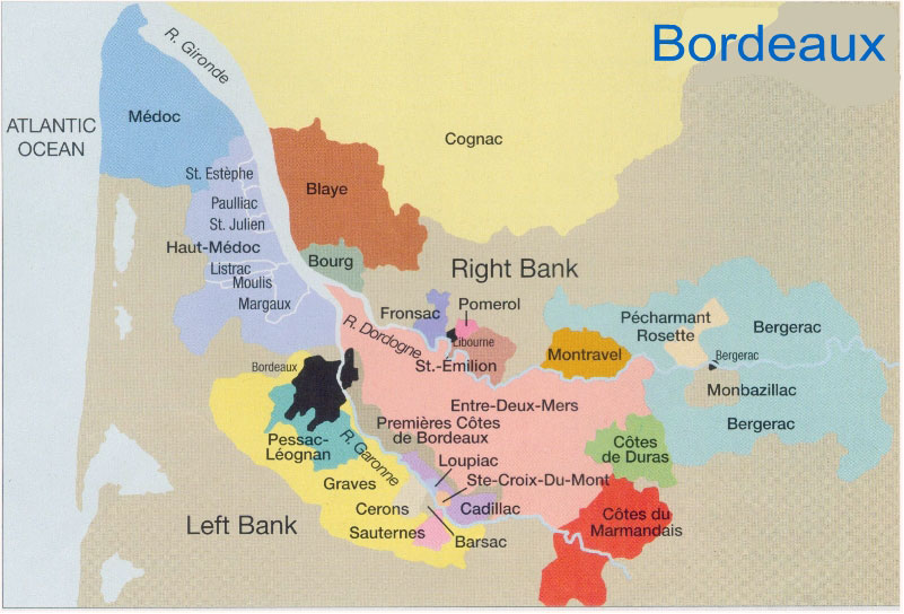

A “Bordeaux wine” is any wine produced in the large Bordeaux region covering the whole area of the Gironde department (please see map). With a total vineyard area of over 120,000 hectares, this makes it one of the largest wine areas in France, only rivalled by Languedoc Roussillon. Average annual production is over 700 million bottles of wine!

90% of wine produced in Bordeaux is red (often referred to as “claret” in the UK), but also sweet white wines (most notably Sauternes and Barsac), and dry whites (most notably Pessac-Léognan) are made. In much smaller quantities, there is some rosé and sparkling wines (called Crémant de Bordeaux). There are over 8,500 producers, or “Chateaux” and 54 different appellations.

GEOGRAPHY & CLIMATE

The climate of Bordeaux is maritime (mild winters, warm but potentially humid summers and autumns). Very importantly the whole region prospers thanks to the amazing sand dune “Dune du Pilat” to the west (on the Atlantic Coast). At over 300 feet in height is not only the highest in Europe but acts as a vital windbreak and climate moderator, without which the quality of the region’s wines would undoubtedly suffer.

The main river – the Gironde – splits the region into two, hence the term “Left Bank” – made up of the Médoc, which includes the prized sub districts of St. Estèphe, Pauillac, St. Julien, Margaux and Pessac-Léognan (Graves), along with sweet wine areas of Sauternes and Barsac. The “Right Bank” is much further inland. It is a far bigger area, and the two most important communes are Pomerol (which is small) and St. Emilion (which is large).

The soils of the left bank are especially poor, with deep gravel (ice age) beds and no real topsoil. The right bank is less gravelly with more clay and loam. The soils of Sauternes/Barsac are less gravelly with more loam and some sand. In simple summary terms, the key black grape for red wines of the Left Bank is Cabernet Sauvignon, in the Right Bank it is Merlot. However, this does not mean the wines here are mono varietals – they are nearly always blends and this blending element is critical to the style and quality of these areas but also highlights the differences between estates within each area as they adapt their own formula to differentiate themselves from neighbours, whilst reflecting the vagaries of each vintage. The leading white grape is Sauvignon Blanc – many in Bordeaux claim its spiritual home was Bordeaux not the Loire Valley. The other important white grape is Sémillon, especially for the dessert wines. As with the red wines the whites are nearly always a blend not a mono varietal.

BOREDEAUX’s DICHOTOMY

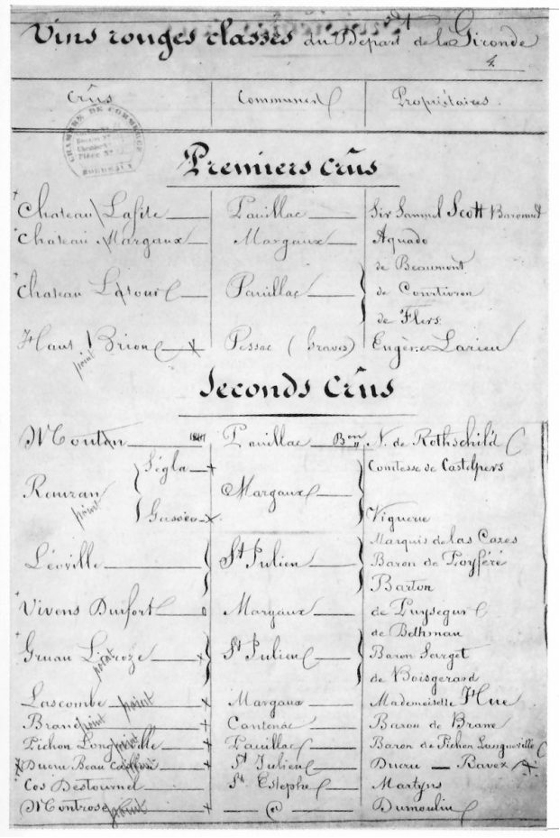

Bordeaux’s reputation is a paradox. The 1855 Classification cemented in place the reputation of 60 Médoc châteaux and one in (then) Graves. It also included an additional 26 Sauternes and Barsac sweet Châteaux – as in those days sweet wine was regarded as the finest of all wines from Bordeaux. Then Château Yquem (for example) was classified as the greatest of all Bordeaux estates. In this classification they ranked the red wines in a tier of five layers or great growths (Cru Classé) – with “Premier Grand Cru Classé” being the highest. These included Chateaux Lafite-Rothschild, Latour, Margaux and Haut-Brion (then a Graves). In 1973 Mouton Rothschild was elevated to join the Premier Grand Cru Classé.

In Sauternes there were three grades – Yquem as “Superior” Premier Cru Classé, then First and Second Growths.

Since then there has been much debate about the classification. The irony has been that although some say that Ch x should be promoted (or demoted) the majority tend to agree on the 61 selection within the Cru Classé list – sure some have gone up and down in reputation, but that has often been down to lack of investment, or a poor winemaking period, rather than an intrinsic error in selection. I think they did a good job back in 1855.

In 1932, the better (non) Cru Classé Médoc châteaux created a new category called Cru Bourgeois which was, in effect, a sandwich fill between Cru Classé and the everyday estates, which are generically referred to as “Petits Châteaux”. However, in recent years fractional in-fighting about the hierarchy within the Cru Bourgeois category has led to a number withdrawing from the classification. In 2010 it was reintroduced as a one tier, annually awarded category.

Turning to the “right bank” to date Pomerol has never had a formal defined Cru Classé system, but St. Emilion did so (maybe theatrically) in 1955. Here they developed a four tier system – which included a Premier Grand Cru – split A (led by Ausone & Cheval Blanc) and B, and then a more permanent Grand Cru Classé system, supported by an annual review Grand Cru classification. Recent headline promotions to Premier Grand Cru Classé A have included Châteaux Pavie and Angélus, so it is the most fluid of all Bordeaux classifications, which I think is to their credit.

In Pomerol, the top three most recognised and sort after growths are Pétrus, Le Pin (part of Vieux Château Certan) and Château Lafleur. Other great growths include Vieux Château Certan (itself), L’Evangile, Trotanoy, L’Eglise Client amongst others. Because the area is so small, and vineyards produce so little the rarity aspect has accentuated the prices for these wines too.

In what was called the “Graves” district there was, over time, a formal pressure and request to differentiate the top estates from the rest – and in 1987 the sub district of Pessac-Léognan was created which included all the greatest estates (by definition – no surprise). What is unique about this area is that it makes both high quality dry red and white wines – and in 1959 this was formally recognised in their own Grand Cru Classé system, to include both colours (unique in Bordeaux). There are no first or second tiers, but Châteaux Haut-Brion and La Mission Haut-Brion (both under the same ownership – and for both red and white) are universally accepted as the region’s greatest growths. Other stars include Haut-Bailly (red), Domaine de Chevalier (red and white), Pape Clément (red and white), Fieuzal (white) to take as few examples.

In part II I will look in more detail at the regions and their wines and how the blending of grapes and production techniques affect quality and style.

There will be more selections from the Wine Trust list in this part as a result, but I cannot finish the first part without highlighting what for many of us is arguably the more important area of this region – finding a consistently affordable producer and style which is good. Whilst it is easy to admire the famous names and Cru Classé in a Bordeaux “beauty parade”, the more workhorse estates and producers who really deliver deserve a wholehearted pat on the back. Wine Trust have long followed the excellent estate of Château de Fontenille. Year after year this producer delivers real Bordeaux style and fine quality at an attractive price. This Merlot based blend hits the button and simply over delivers for the price. I heartily recommend it to any red Bordeaux lover.