[twitter style=”horizontal” float=”left”]

[fblike style=”standard” showfaces=”false” width=”450″ verb=”like” font=”arial”]

Bordeaux is arguably the best-known wine in the world after Champagne, but it has an image problem. Since the 1980s, younger people prefer to drink wine from elsewhere – usually the New World, meaning Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Chile, Argentina, America. Our consumption of Bordeaux has decreased from 50% to only 25% since the 1980s. This sea change in wine consumption was provoked to a certain extent by a blind tasting in 1976, the celebrated ‘Judgment of Paris’ in which French wine experts, somewhat embarrassingly, preferred Californian wines to French.

I was invited on a press trip to a newly refurbished Bordeaux city during the harvest. This year has been particularly good: the vines displayed large low-slung grapes in abundance. The weather – just enough rain, plenty of sunshine – has helped. The winemakers were relaxed and welcoming, and had time to bring in the harvest. Some years they don’t have much time. A winegrower recalled a year in which they had only two days, at the weekend, to pick the grapes. Everyone gets involved (nan and granddad, friends, family, children, the village) to avoid the whole year’s crop being merely next year’s fertiliser.

Bordeaux is incredibly complicated; the inaccessibility may be one of the reasons that it isn’t as popular as before. This trip gave me an opportunity to get stuck in and attempt to unravel Bordeaux wine. This blogpost is Bordeaux for dummies like me and some of you.

History:

Bordeaux is the largest wine producing area in France, accounting for 45% of all French wine production and 1.5% of the world’s wine production.

It is also a historical port that has always had strong links with the UK. It used to be English in the time of Eleanor of Aquitaine, the Wendy Deng of her era, who was first married to the King of France, then the King of England. As a result, many of the chateaux and the wine exporters were British. The British used to drink mainly French wine and Bordeaux was known as ‘claret’.

The late nineteenth century was a turning point for European wine, when Phylloxera, an aphid from American vines, gradually destroyed virtually every vineyard including Bordeaux. The solution was found by grafting European grapes onto Phylloxera-resistant vine roots. (This technique is also used for tomatoes, grafting fragile varieties onto blight resistant roots.)

Complex system of wine classification:

In 1855, Napoleon III decided to start a classifying the best Bordeaux wines by ranking them from first to fifth. These classifications were known as ‘crus’, which is French for growth. ‘Premier cru’ thus means first growth and so on. Bordeaux wines are divided into ‘chateaux’, which directly translates into English as ‘castle’.

The ‘premier crus’ were the best castles or chateaux. You might assume that ‘premier cru’ referred to the quality of the wine, but instead it indicated the value of the building and the surrounding land. This meant that the richest chateaux became premier cru, not necessarily the best wines or the best wine makers.

There are:

- 5 Premier Cru reds

- 11 Premier Cru whites

- 1 white Premier Cru Supérieur

- All of the white premiers cru are sweet

.

Maxime Saint Martin, president of Crus Artisans at his winery Chateau Vieux Gabarey.

New Classifications:

All Bordeaux wine bottles say Grand Vins de Bordeaux, which, while sounding ‘grand’, means nothing other than it is grown around Bordeaux. The words ‘vin de Table’ have been replaced, since 2010, by ‘Vin de France’.

Nowadays there are new growths or crus:

- Cru Bourgeois. These are good quality wines that weren’t included in the 1855 classification.

- Cru Artisan. A new classification meaning that traditional craft techniques have been used in creating the wine, e.g. daily presence of the wine maker and hand-picking. This is similar to what has happened in bread, in that boulangeries in which everything is made by hand are sign posted as ‘boulangerie artisanal’. There are 44 estates that are part of this new growth.

Labels

Unlike New World wines, French wines don’t have the name of the grape on the front label. As a concession to modernity, Bordeaux wine makers are starting to have back labels on bottles with the name of the grape written in tiny letters.

Why is this? Bordeaux specialises in blends. Theirs is the art of the winemaker rather than the grape. What makes a great wine? Not just one grape or ‘cepage’. It’s rare to find 100% of one grape (a monovarietal) in a Bordeaux bottle.

People often order a wine by the grape now. ‘Oh, I fancy a Chardonnay.’ It’s easier than remembering a hundred different chateaux or appellations. (Actually, Bordeaux has 65 different chateaux.) This lack of grape on the label is rather old fashioned, as is pictures of castles on labels. Half of them aren’t even proper castles. Sometimes it’s just a house. Bordeaux should probably be divided into two drinks: Premier cru and the rest (see ‘It’s expensive’).

The language

The world of wine, just like the world of gastronomy, speaks French. One of the reasons the British have taken to New World wines is because, for the most part, their language is English. It’s a great deal easier to say I’ll have a bottle of Cloudy Bay rather than a bottle of Pessac-Leognan, for instance.

Below is a little lexicon to make things easier.

Appellation: from the French appeler (to call); the name of the place where the wine is grown

Cru: growth

Varietal: type of grape

Cepage: grape

Monovarietal: one type of grape rather than a blend

Types of wine in Bordeaux

Bordeaux, although traditionally a white wine area in the past, is now most famous for red wine. But that is not all. They produce several other kinds of wine:

- Red

- White

- Rosé

- Clairet (a bit darker than rosé, a descendant of the English word ‘claret’, a light red Bordeaux)

- Cremant (sparkling white or rosé)

- Sweet white

Many of the vines are harvested by machinery, the grape vines pruned in such a way that the grapes hang below, making it easy for mechanised picking.

In sweet Bordeaux however, all the picking is done by hand, an expensive and lengthy process. However, true to modern France, where everyone only works 35 hours a week, pickers do not pick at weekends. If, because of the weather, they are obliged to work at the weekend, they are paid double, which makes it even more expensive. I have to say, I found this kind of legal restriction in agricultural work quite surprising. If you want to do ‘the vendange’ for sweet wine, it’s better if you are local, because they don’t pick every day. They usually pick in three stages, as gradually the grapes shrivel and rot.

Try a claret from the Pessac Leognan left bank region: 2012 L’Esprit de Chevalier rouge £28

Types of grape used in Bordeaux

Red wines are allowed to use the following 6 grapes:

Merlot: a cross between Cab Franc and Magdeleine Noire. Merlot is ‘occitan’ (the Southern French language) for little blackbird. Large blue-black grapes. Good yield and adaptable. More popular on the right bank.

Cabernet Franc: the ancestor of the Cabernet grape, the most ancient in Bordeaux. Originally from Northern Spain. Posses small round grapes.

Cabernet Sauvignon: Smallish grapes with thick skins, packed tightly on the bunch. Easy and robust to grow. One of the world’s most popular grapes.

Malbec: fragile, thin-skinned, plum-like flavour, deep red inky colour, tannins.

Petit Verdot: used in small quantities to add structure to blends in certain Bordeaux chateaux. A late ripener, it contains tannins, a deep red colour and banana/violet flavour. An ancient grape, possibly of Roman ancestry.

Carmenère: one of the original Bordeaux grapes, the ancestor of cabernet, was thought to be extinct but discovered in Chile, probably taken there pre-phylloxera. Some Bordeaux winemakers are growing this grape again. I met Marc Milhade at Chateau Recougne (below) who has reintroduced Carmenère at his estate.

If you fancy tasting this produce of this grape, Winetrust carries a Chilean Carmenère wine: 2015 Adobe Carmenère, Emiliana, Organic £7.75

White wines use a blend of:

Semillon: Late ripening medium-sized bunches. A typically Sauternes grape. Can be used for dry and sweet white wines. This is used in creamier style whites from Pessac-Leognan.

Sauvignon Blanc: Originally a wild vine from Bordeaux. Thin skinned, yellowish grapes, growing in tightly packed bunches. Likes limestone soils. Passionfruit.

Muscadelle: similar smell to Muscat grapes but not from the same family. Very fragile, prone to pests and as a result not grown much. Known as Tokay in Australia.

Ugni Blanc: rarely used. Adds acidity.

Colombard: again used in small quantities, adds structure and tropical fruit.

Sweet wines

Sweet wines are a whole other category in Bordeaux, using the micro climate of misty mornings and dry afternoons to attract Botrytis or noble rot to the grapes. The hand picking is a complex and trained procedure, done in at least three sessions. The resultant wines are sweet, rich, heady and perfect with cheese, foie gras and Asian food.

‘Sweet wine is very complex,’ says botrytis expert and Bordeaux professor of oenology Jean Christophe Barbe at Chateau Laville, his family estate. I called him the Professor of Rot.

‘Most wines have 1,000 aromas but sweet wines, because of the noble rot, have closer to 3,000. The grapes we use for ‘pourriture noble’ are thin skinned – it attacks the skin first. For noble rot we need dry conditions on the berries. If it is too wet, grey mould appears. However in Bordeaux we are not allowed to irrigate unless you have a special permit from the authorities. Irrigation is very expensive, 15k euros per hectare.’

We sat at a white clothed table in a dark room, tasting wines that danced with banana, grapefruit and orange zest flavours while Monsieur Barbe’s elderly aunt chatted in a back room.

Try this Sauternes sweet wine which is fantastic with a cheese board: 2009 Chateau Laville £17

Geology: Left bank and Right bank

Another categorisation that makes things confusing is the left/right bank thing. Partly because there is another famous left/right bank situation in Paris. Historically the left bank of the Seine was where the bohemian intellectuals and artists hung out and the right bank was the old money, the museums and the bourgeoisie lived. Of course nowadays both banks in Paris are super posh.

In Bordeaux the river dividing the two banks is called the Gironde. Here it’s the left bank that is wealthy, prestigious and premier cru, while the right bank is more rustic.

Left bank wines are planted in gravelly ground with limestone bedrock. This is better for the Cabernet grape and leads to wines that age well.

Right bank wines are planted in less gravelly soils with some like Pomerol containing clay and sand. Their wines, mainly Merlot grape, are more tannic. But the reputation of right bank wines has improved.

In the 90s, the right bank produced a movement called ‘les garagists’, i.e. wine actually made in garages by hand (similar to the wine punx who I visited last year) where young wine makers made wines that were more accessible, and drinkable earlier.

Ultimately it’s all about the dirt that the grapes grow in. We were driving through the Medoc region on the left bank looking around the countryside: on one side of the road there are fields with gravel and a slight rise. This is where all the posh chateaux lie.

The other side is closer to the Gironde, subject to flooding, with water and reeds. This fertile land is used for corn or grazing. It’s worth much less than the gravelly land. Grapes prefer infertile land that they can struggle through.

Then there is this other weird region, south of Bordeaux, that isn’t left or right bank called ‘Entre Deux Mers’ or ‘between two seas’. Actually it is between two rivers and was originally most likely named as ‘entre deux marées’ or tides.

Thibault Despagne of Chateau Tour de Mirambeau in the Entre Deux Mers region.

Try this white Bordeaux from Entre Deux Mers: 2013 Chateau Lestrille-Capmartin £12.

How long can you keep it?

The reputation of Bordeaux wines is that they must be laid down and stored for years before you can drink them. Which is true up to a point. It’s one of the best things about Bordeaux, and a reason for the high price. These are investment wines that will last decades and in the case of sweet white wine, a century or more.

This is another reason why Bordeaux wines appear inaccessible. Most of us just want something for that nights dinner. Most of us, especially if we live in the city and have limited space, don’t possess a cellar. People simply can’t store wine anymore.

The purpose of this trip was to discover drinkable Bordeaux wines priced from £5 to £20. (Seriously there’s literally no point spending less than a fiver on a bottle of wine, most of the price is taken up with tax and about 50p on the actual wine).

If you are a swotty expert you’ll know all the best years off by heart, but for the rest of us, here is a guide to the best vintages.

It’s expensive

A good premier cru Bordeaux costs a great deal of money. In a good year this means that the top chateaux make a great deal of money but the reputation of mid-price Bordeaux suffers. The thinking goes: Bordeaux is great when it’s expensive but not terribly palatable when it’s cheap.

I had to confess at the beginning of this trip that I never buy Bordeaux. Given the choice at an off-license or a supermarket between a £7 Australian or a £7 Bordeaux, I’ll choose the Ozzie. I suppose my tastes were formed in the 90s when the reputation of Bordeaux sank. Often the wines were disappointing. (For all the noise about joining the EU, the price of wine didn’t come down. Wine remained the same price because most of it went to the Exchequer. In fact the single most positive thing that Remainers could have done to encourage people is to lower the taxes on decent European booze.)

Nowadays many of the premier crus are owned by big corporations such as Axa insurance or banks like Credit Agricole. Fine wines are big money. However do try growths other than premier cru, they have improved hugely since the 1980s, equalling any new world wine for taste and value.

Try this Left Bank cinquiéme cru Grand Cru classé: 2007 Chateau Cantermerle £32

Climate Change:

Bordeaux, like other wine regions is affected by global warming. Winemakers are preparing for this eventuality by changing grapes, changing blends and allowing watering. Formerly cold regions are now becoming suitable for wine. In Bordeaux, their ancestors picked the grapes on August 28th. In 1980, they picked on October 28th. Winemakers have no insurance, if the crop fails, that’s it. A farmer lives by the weather: most of the growers had at least four weather apps on their phones.

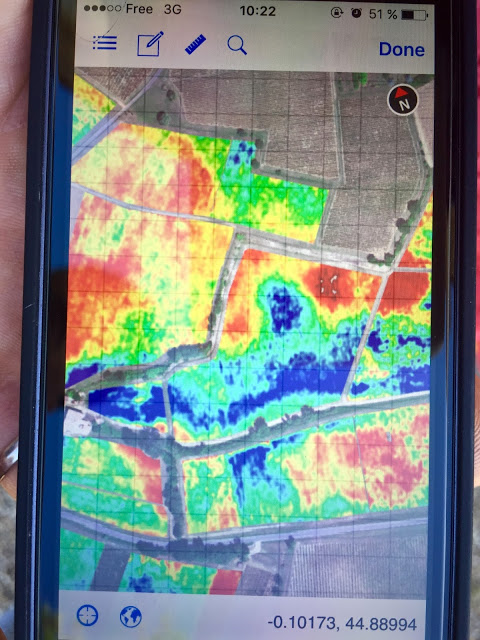

One wine maker had a fascinating heat seeking app in which he could see which vines needed to be picked on his estate by the colour.

In Bordeaux it is illegal to irrigate, they regard that as a New World ‘cheat’ but in 2006, the regulations were changed. In certain years, they can apply for a special irrigation permit, but this is bureaucratically difficult plus expensive. To imitate the effects of 20 minutes of rain, you need between 100 and 200 cubic metres of water per hectare. And it costs 15k euros per hectare.

Pruning:

There are different ways of pruning a grape vine. You want to encourage the grapes to grow in a line underneath the vine so they can be easily picked. The shape and style how vines are trained means that a wine expert can, at a glance, even from a distance, tell exactly which kind of grapes are being grown in any vineyard.

Spur training: two to three renewal spurs with two buds. The stems are usually thick and gnarly.

Semillon is pruned in a ‘cote’ shape.

Other grapes are pruned into a single or double guyot, which means they have a T shape or an L shape with arms that branch out one side or both sides.

Is Bordeaux old fashioned?

While I was there, I did a Twitter poll asking people how they would characterise Bordeaux: as either classic or modern. Classic won out, in fact modernity got no votes whatsoever. This old world wine has a reputation for being old fashioned. But techniques and equipment in Bordeaux nowadays are cutting edge. Younger Bordelais winemakers, such as those we met on the left bank, in the Medoc, making Cru Artisan, are just as inspired by Australian wines as French winemaking. They are modernising their labels, using back labels as well as front, naming the grape blend percentages, experimenting with oak and unoaked wines. Bordeaux is modernising in another area: for years wine was dominated by men, but most of the wineries we visited had female wine makers.

One lesser known Bordeaux wine in Blaye on the right bank, the young female winemaker, Jessica Aubert at Chateau Nodot, following the latest trends in winemaking, was playing music to the vines twice a day, using special sound waves that are supposed to appeal to grapes. She, like many others, have gone biodynamic, planting and harvesting with the phases of the moon. Bordeaux winemakers are increasingly turning to organic techniques, marshalling the old as well as the new.

Jessica Aubert plants roses at the end of each line of vines, to give early warning of disease.

The Future

However there is a long way to go. We found at the young trendy Bordeaux restaurants, they barely carried any Bordeaux wine, preferring to offer exotic foreign, obscure or natural wines for instance, forsaking their own region. The new Bordeaux wine makers need to spread the message to their own people too. Do try some of the Bordeaux wines recommended in this post to further your own wine knowledge. After all, it’s Bordeaux that is the starting point for most wine styles and techniques in the global wine scene.

[twitter style=”horizontal” float=”left”]

[fblike style=”standard” showfaces=”false” width=”450″ verb=”like” font=”arial”]