Part Two – Rosé and White Winemaking, and Aging of Wine Prior to Bottling

Rosé Wine

And the longer you leave the black skins in contact with the juice the darker the colour becomes. To put this into context, as little as 12 hours will see a rosé “staining” in the wine – typically used in Provence to make their classical pale rosé, as exemplified by the superb, cultish Whispering Angel from Château d’Esclans – https://winetrust.co.uk/shop/whispering-angel-cotes-de-provence-rose-chateau-desclans/.

After 36 hours – a deeper rosé hue will be achieved, if desired. If you wanted to make a deep, dark red, by contrast, the contact period could easily be 2-3 weeks or longer. And then there is the effect of the grape variety itself.

Certain varieties, such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah/Shiraz have much deeper colour pigments in their skins than say Pinot Noir and Grenache. Therefore, Cabernet skins left in contact with their juice for 36 hours will produce, on average, a deeper colour than say Grenache over the same period.

So, the winemaker will judge the moment when they are happy with the depth and hue of the (rosé) colour; at which point they draw off the juice and separate the skins (which no longer are needed). They then finish the fermenting process as though the wine were a white. In most cases in the world rosé wines are made without any contact or aging with oak barrels to preserve and enhance their lively fruity character.

All “Rosé” Wine – but just look at the different levels of colour intensity

White Wine

A classic shot in a white winemaking facility – using a mix of inert stainless-steel vessels and barrels. Chardonnay is often fermented and aged in oak barrels, whilst aromatic whites – eg Sauvignon Blanc and Riesling will be mainly fermented in stainless steel to preserve the delicate fruity esters and flavours – and because they do not want any oaky notes. White wines are also fermented at lower temperatures (16-22°C), with reds somewhat higher (28-32°C). This is to highlight and preserve the fruity esters which make so many white wines attractive. The one white grape (as discussed in a previous blog) that benefits consistently from being barrel fermented and aged though is Chardonnay.

Filling a barrel (top) prior to white wine fermentation, the dead yeast residue left behind (Bottom) after, by contrast, fermenting in stainless steel

Once fermentation has finished, most red wines (and many Chardonnays) are then moved to barrels to complete their maturation. Barrels come in all shapes and sizes. Above is the most common size: 225-250 litres. The source of the oak, and whether the barrel has been used previously, is important in the effect it has on the developing wine – not least on how “oaky” it will make the wine smell and taste.

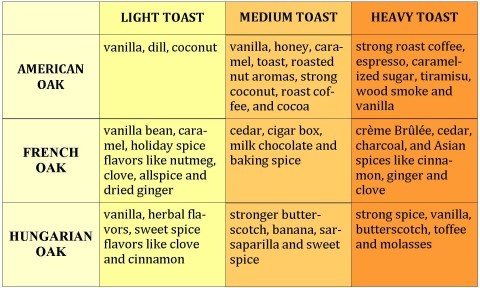

All barrels are heated during their construction and this results in varying levels of charring inside. This contributes to the “smoky” or “toasty” smells and flavour found in the wine. In fact, winemakers when ordering their barrels will stipulate whether they want “Low”, “Medium” or “High” toast in the casks. And the table outlines some of the varied components which can be imparted into the wine overtime.

Of course, the newer the oak, the more “oaky” the wine will be simply because the wine is encountering the oak for the first time. In addition, certain oaks have naturally stronger characteristics – for example American oak is naturally higher in elements of “vanilla” flavour than other species.

But of course, it you are looking to make fresh and fruity white wines – eg Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling, Albariño – then oak is the last thing you need to use as you want the natural and fragrant fruit flavours of these grapes to showcase themselves – not the oak override them.

This is a much larger, older barrel, imparting no oak character to the wine. In effect, it has become a storage vessel. This suits some wine styles – both red and to a lesser degree white – better than smaller barrels, where a winemaker is actively looking for a gentle level of mildly oxidative handling in the process. And of course, in the old days, wood (and large ceramic jars or pots) were the only available resource to make and store wine in.

A classic stainless steel unoaked white wine from Wine Trust is the simply outstanding crisp and citric Duffour Domaine Côte de Gascogne

And a classic barrel fermented, and oak aged style is the superbly textural and very well-balanced Reserve Chardonnay from top South African producer Chamonix

Back to red winemaking ….

This is a “basket” press: once fermentation has been completed and the young red wine has been drained off the skins, the remaining black skins are pressed to extract the last of the wine that they contain. This is called “press” wine in red winemaking and is very dark in colour and high in tannin. This wine will be aged separately from the “free run” wine which has already been drained off. This gives the winemaker the option to increase the colour and/or tannin by blending some press wine back should they think the finished wine requires this.

This is a “bladder” press, used for some reds and almost all whites. A large bladder fills with air, pressing the contents gently and evenly, with gradually increasing pressure. This gently squeezes out the juice from the berries.

And this is what is left at the very end – the squeezed skins, or marc in French. It can again be used to make compost for example.

Barrel halls can still look quite traditional. Cool, humid underground cellars are perfect for maturing wines – a process that takes anything from six months to three or more years.

Winemakers typically check the maturing red wine barrels at regular intervals and top them up as some of the wine evaporates during the maturation process. This also gives the winemaker the important opportunity to taste how each barrel is evolving and start to make decisions about when to bottle, and which cask to blend with which prior to bottling. In regions where more than one grape variety is used in the final blend – a classic example is Bordeaux with Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot – each variety will be aged separately in individual barrels at this stage.

It is sometimes necessary to move wine from one barrel to another, or from barrel to stainless steel tank. This cellar hand is using nitrogen gas to move the wine without exposing it to large amounts of oxygen.

Here wine is being moved from one barrel to another deliberately exposing it to oxygen to aid in the maturation process. By doing this the tannins in the red wine will be softened through controlled, additional contact with oxygen. This also assists in clarifying the final red wine as the wine is drawn off the (hazy) lees which collect in the “belly” of the previous barrel.

Those wines which see no oak at all, but are made and kept in stainless steel tanks, do so to preserve the fresh fruity characteristics. This is especially true for “aromatic” white wines (as mentioned before), but a few red wines are also made without contact with oak to promote their intrinsic fruit flavours and aroma. A couple of good examples of this approach are the majority of Beaujolais (in Burgundy) and Valpolicella (in Veneto).

Finally, the wine is ready, blended and prepared for bottling. Often, finings (a clarifying agent) are added and filtration is used to make the wine bright and clear, and to remove any risk of microbial spoilage. The glass on the left has been filtered; on the right you can see what it was like just before the process.

Let’s finish with a classic oak aged and bottle matured red wine – the beautiful velvety Reserva Rioja from the iconic Marqués de Murrieta

Nick Adams 2020 08